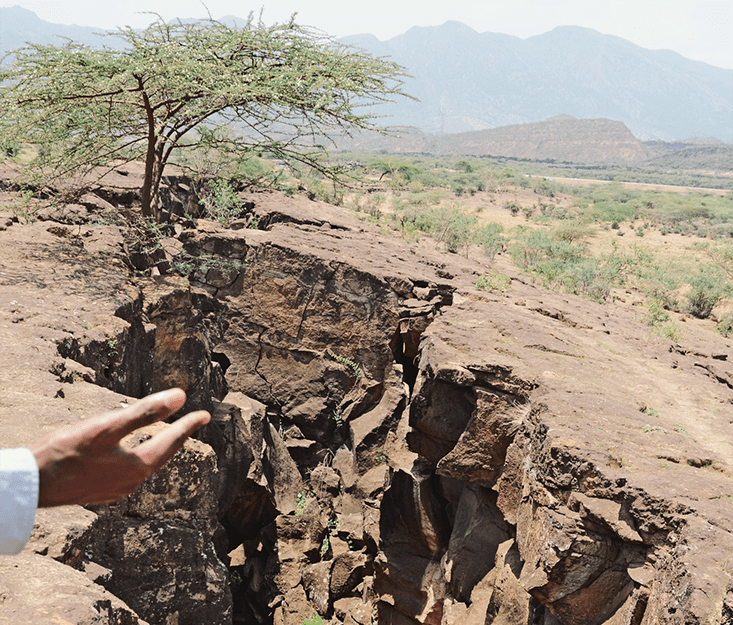

Two hammers, two shovels, four rifles. They carried their own tools. Zeresenay Alemseged, a young and driven Ethiopian fossil hunter, joined by four armed soldiers and a government official, was on a mission to the Afar Depression, a region shaped like a tornado in Ethiopia’s Great Rift Valley. The Afar is bone-dry, scorching hot, and riddled with scorpions and vipers. It is regularly shaken by earthquakes and sinking deeper into the Earth as the converging tectonic plates beneath it pull apart, and molten magma bubbles up through the cracks. When the magma cools, it forms sharp, basaltic blocks.

Along the road, the boulders blocked Alemseged’s path. He had to stop the car, lift the boulders, drive further, repeat. Dry riverbeds were smoother, but frequently the tires sank in the fine sand, and the men, sweating in the afternoon sun, pushed the jeep onward.

Alemseged was headed to the most dangerous spot within the Afar, which even Indiana Jones-types avoided because of constant conflicts between local tribes. The armed soldiers were his security. Alemseged had no salaried scientific position, and refused to accompany teams led by accomplished researchers going to safer areas with fat grants. If he struck out on his own, he felt sure he could discover academic gold: ancient traces of humankind’s past. This meant funding the expedition out of pocket. “I was the driver, so I didn’t need to pay a driver; I was the cook, so I didn’t need to pay a cook; and I was the only scientist,” Alemseged said.

His aim was to explore an area called Dikika, across from a bank on the Awash River where an American paleontologist, Donald Johansen, had discovered Lucy in 1974. Her ancient skeleton’s partially human, partially chimpanzee features were a clear indication of our descent from the apes. Dikika was the logical next place to look for more fossils, but no one had done so because of the risk presented by battles waged over water and land between the Afar and the Issa, pastoral tribes who inhabit Dikika. But Alemseged, who goes by Zeray (pronounced Zeh-rye), was not deterred.

Alemseged’s bare-bones team reached a vast plain of sand and volcanic ashes. He knew this sediment yielded the type of fossils he was after. In December of 2000, one of the men spotted the top of a skull the size of a small orange in the dirt. Slowly, over a period of years, he and his colleagues carefully unearthed a petite skeleton of a child who had likely died in a flood and been buried in soft sand, 3.3 million years ago. She was a member of Lucy’s species, Australopithecus afarensis, from a period about halfway between today and the time when our lineage went one way and that containing chimpanzees went the other. In 2006, Alemseged and his colleagues published their findings in Nature.1

The child was named Selam—a word for peace in several Ethiopian languages, a wish to end the fighting in Dikika. Selam’s gorilla-ish shoulder blades and long fingers betrayed a penchant for swinging on braches. But bones at the base of her head showed that she held it upright and therefore walked on two legs. The size of her skull suggested her brain developed slowly through early childhood, a distinct characteristic of humans from long before modern humans evolved.

“It’s the earliest child in the history of humanity,” Alemseged said, enunciating each word slowly. “That discovery was 100 percent Ethiopian. It was by Ethiopians, on Ethiopian land, led by an Ethiopian scientist.”

Alemseged, 45, was describing his scrappy first expedition to Dikika for me in a sparsely furnished conference room in the new facility for “antiquities research and conservation” beside the National Museum in Ethiopia’s cool, green capital, Addis Ababa. It was August and the facility was a hub of activity. Some of the world’s foremost experts on early human evolution rushed from room to room, hurrying to collect data from their fossils before the school year started. They were here, instead of in the field, because heavy seasonal rains had flooded the dry riverbeds on which they normally drive to the Afar.

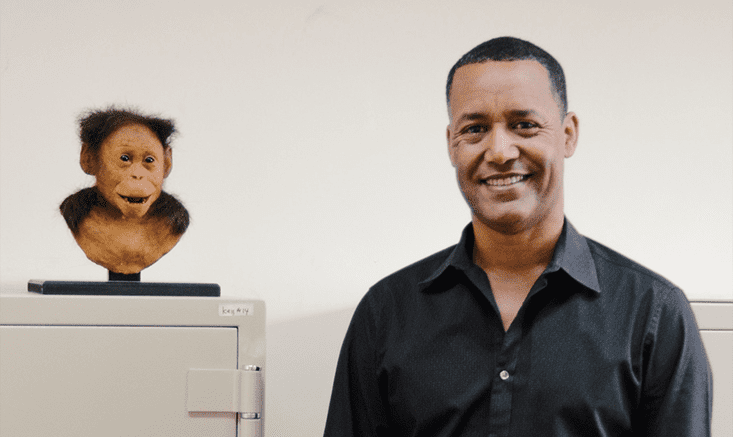

Alemseged wore two beaded bracelets on his wrist—one with the word Ethiopia spelled out in yellow beads on a black background. With his square jaw and confident demeanor, he looked more like a Hollywood actor playing an archeologist than the serious scientist that he is. When he’s not doing fieldwork in Ethiopia, he directs the anthropology department at the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco, where he lives with his wife and two kids.

I had come to Ethiopia in search of my own deep vision of humankind’s history and fate. A flood of new discoveries coming out of the country have suggested that human traits occurred in ancient members of our tribe, the hominids, long before Homo sapiens entered the scene 200,000 years ago. I wanted to meet the native and foreign scientists responsible for shifting our origins backward in time. Soon after I arrived, Merkeb Mekuria, an anthropologist and curator at the Ethnological Museum in Addis Ababa, greeted me. “Welcome home,” he said.

Charles Darwin knew humans evolved from apes, but he died before the strongest fossils that prove our connection with primates had been discovered. In The Descent of Man he wrote, “Those regions which are the most likely to afford remains connecting man with some extinct ape-like creature, have not as yet been searched by geologists.”

A century later, Lucy helped confirm Darwin’s conjecture. By that time, a vision of our origin had been born, and her skeleton was assumed to fit the story. It’s one that (wrongly) persists today: Apes climbed out of the trees and ambled onto their feet, dragging their fists, as the climate warmed and turned forests into grasslands. Yet it was clear to paleontologists that many more fossils were needed to test this hypothesis. That’s around when Ethiopian paleontology by Ethiopians got started in earnest.

The bones of distant members of our human family are buried in tumbles of sand in Africa, and Ethiopia has unbeatable archives. The pages of human prehistory are preserved in its layers of mud, bones, and basalt. In the Afar, the magma that periodically bubbles to the surface serves as a timepiece because the chemical composition of every volcanic rock betrays the stone’s age. Over time, the ratio of the gases trapped within it changes at a fixed, known decay rate, so you can determine whether it covered the land 4 million years ago or yesterday. Fossils located between two layers of volcanic ash and lava were left by animals that lived within that time range. Individuals belonging to Lucy’s and Salem’s species have been found in layers dating from almost 4 million to 3 million years ago. That means they lasted five times the duration of our own species so far. “Can we do at least as good as this primitive species?” Alemseged asked.

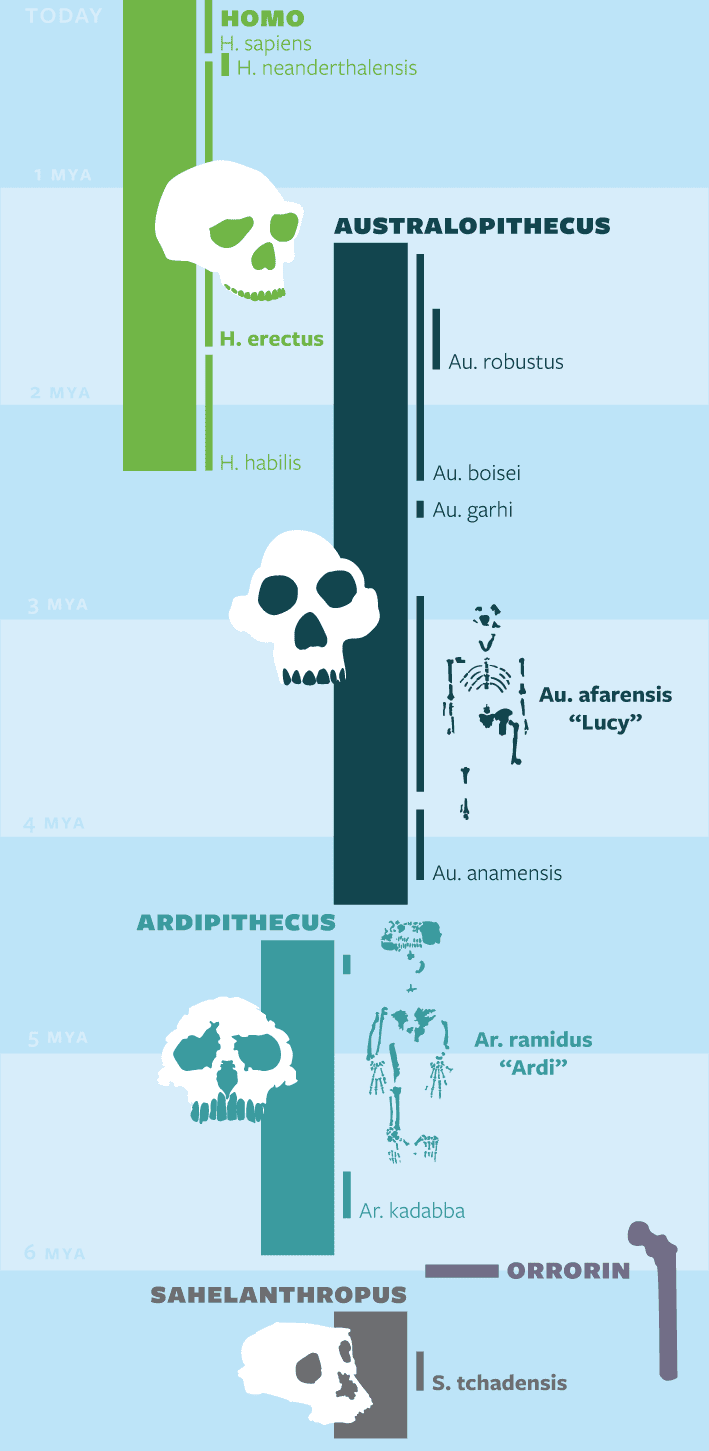

FAMILY HISTORY: Of about 20 known hominid species (members of humankind’s family tree, including us), half have been found in Ethiopia. Only a fraction are pictured here. Lucy’s species, Australopithecus afarensis, survived for longer than we have thus far, and recent studies suggest they were far more advanced than previously believed.

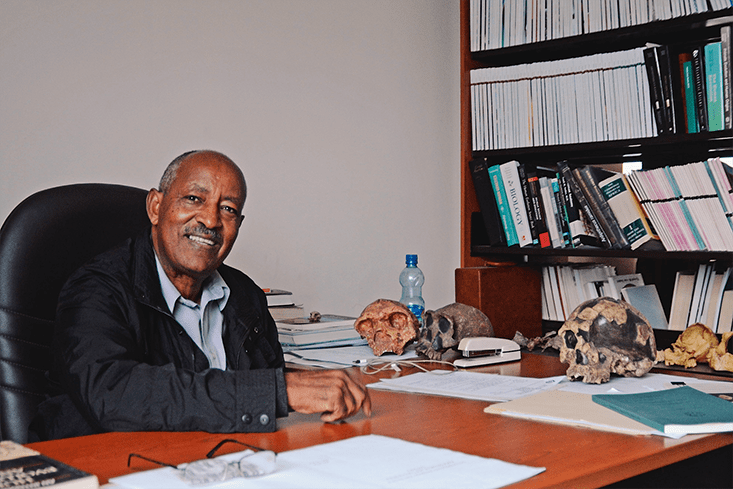

In 1978, a student at Addis Ababa University, located in Ethiopia’s mountaintop capital, was told to summarize the information on fossils discovered by Western scientists in the Afar. The student, Berhane Asfaw, had not chosen the job. It was assigned to him—as jobs were in those days—by the Derg, the communist regime that ousted the long-standing Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie, and threw Asfaw, and thousands of other dissenters, in jail. Of six students locked up alongside Asfaw, five were executed. Asfaw was set free.

Asfaw found solace in the geology and archeology reports he combed through. Desmond Clark, a geology professor at that time at Addis Ababa University,observed that Asfaw had done a thorough job, and convinced him to pursue a graduate degree. Clark invited his mentee on an expedition to the Afar with Tim White, then a skinny, ambitious junior faculty member at Berkeley. Before the trip was over, what had begun as an assignment had become Asfaw’s life passion.

“Every second, I was learning,” Asfaw recalled, his palms swinging upward along with his thinning eyebrows. “I had been a geology student so I knew which rocks were old, but it was such a surprise to see fossils coming out of the sediments. It wasn’t just one or two, there were plenty, and I saw hand axes, and just hundreds of stone tools.” Asfaw was impressed by White, now a leading expert on early human evolution. “He was so hyper, he never got tired,” Asfaw said. The duo got along swimmingly. By 1981, Asfaw was off to Berkeley to finish his Ph.D. Soon after, his young wife followed. They appreciated Berkeley’s diverse and liberal community. On Telegraph Avenue, they giggled at the town’s notorious bohemians.

Meanwhile, between 1983 and 1985, the Derg amplified the devastating effects of a great drought, in which 1 million Ethiopians starved to death. Most Americans learned about the tragedy in TV ads of skeleton-thin children, and Michael Jackson’s “We Are The World,” and Band Aid’s “Do They Know It’s Christmas.” “When I saw all those people gathering to try and raise money to help the affected people, I really felt criminal to be on the outside and not doing anything,” Asfaw explained. “My dream was to come back to Ethiopia and make a difference.”

By 1988, the Derg’s collapse was imminent, and Asfaw was eager to return home. “My plan was to survey the entire Rift Valley from north to south and look for new [fossil] sites,” he said. During the transition from the Derg to the new government, the country became increasingly unstable, and there was growing conflict near the northern Eritrean border. Asfaw kept thinking about the precious hominid fossils that could be lost before they were ever found. He stressed the urgent need to preserve antiquities in grant proposals. With funds from the National Geographic Society, Asfaw organized a team including White, a Japanese friend from graduate school, Gen Suwa, and a handful of young geology, archeology, and history graduates from Addis Ababa University. By the end of the year they were off. “It was the first team with a lot of Ethiopian researchers,” Asfaw said. “We were successful because we knew how to get around and which areas to avoid.”

At one of the sites, Suwa stumbled upon the shiny surface of a molar that was distinctly hominid. Much older than Lucy, the team called the genus Ardipithecus ramidus, based on the Afar word ardi for “ground,” and ramidus for “root.” They thought the species might be the first member of our family to walk on land on two legs.

Then in 1994, one of the young Ethiopians on the expedition, Yohannes Haile-Selassie—who has since become a paleoanthropologist at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History—spotted a finger bone from Ardipithecus ramidus. The team decided to excavate the entire region, and recovered over 100 fractured pieces of a single skeleton, bones from several other individuals, and fossils of ancient animals that lived within the same period, 4.4 million years ago. That’s when the real work began.

At first, the team kept their fossils in the National Museum in Addis Ababa. When it overflowed, they moved them to a canary yellow, stucco building beside the museum, which had housed the Italian government during its brief occupation of Ethiopia around 1940. There, and in an “old moldy building” beside it, White removed hardened silt from soft bones with brushes and dental tools; Suwa took fractured pieces of the skull to Japan where he digitally reconstructed their arrangement with a computed tomography scanner; and Asfaw compared the skull with those of ancient primates and hominids from around the world. During the course of the analysis, a skull from an older member of our ancient family was reported from Chad, but its skeleton was missing. From start to finish, the analysis took 15 years and 47 researchers to paint a full picture of Ardipithecus ramidus—Ardi, for short—and her surroundings. In 2009 they published 11 reports in the journal Science.2

The following year, a brand new, five-story facility for antiquities research and conservation, funded by the Ethiopian government, opened its doors in Addis Ababa. In part, this happened because of years of advocacy from Asfaw and his Ethiopian colleagues, who regularly spoke with the government about the importance of human evolution research. Grants from the United States, Japan, and France helped furnish the building and stock it with equipment. Casually called the museum facility, it abuts the old Italian government building and houses more than 250,000 ancient bones and stone tools, including 11 species of hominids—half of them discovered in the past two decades.

“Berhane deserves a lot of the credit for changing the way things are done, from the old colonial way where Westerners gained access to the countries with these resources, and got publications, but never invested in local scholarship,” White said. “That’s a lose-lose situation because the country loses and so does the science—which is done very well by folks who speak the local languages, know the geography, and understand the culture.”

However, Ethiopia is still a long way from Berkeley. The electricity frequently goes out, which means Asfaw must leave his office when the sun dips below the horizon. The phone lines are dreadful; the Internet spotty. This disconnect to the rest of the world explains why Asfaw is rarely mentioned in magazine articles and books on human evolution, despite his dozen publications in top journals. He’s been offered academic positions in rich countries, where he would obtain a good salary and wider recognition, but he declines. I asked why and he answered with a grin. “I am the most privileged person because I live with the fossils,” he said.

With Ardi, a couple of existing views went up in smoke. Lucy’s predecessor was supposed to represent an earlier step in the chain, an ape-man who hobbled through the type of savannah advertised on Safari brochures. On the contrary, Ardi appears to have been a bona fide bipedal, woodland-dweller. Monkeys and other woodland mammals unearthed where Ardi and her kin were buried indicated that the species spent their days in the woods. Ardi’s big toe remains chimpanzee-like. It’s large and opposable, allowing her to climb along branches. But unlike apes, her toes are arranged in line with her foot to help her step flatly on the ground, and her pelvis is broad enough to anchor walking muscles.

“The savannah hypothesis was perfectly reasonable, until it was like, ‘Oh crap, there weren’t grasslands,’ ” said Amy Rector in the museum facility in Addis Ababa, where she was surrounded by ancient antelope skulls, their long, twisted horns extruding from wooden boxes. Rector underscored another debunked scenario: the idea of a linear progression of humankind. Two years ago, the discovery of sausage-toed foot bones that match Ardi’s, in layers of rock from Australopithecus’ time, show that a range of upright-walking species occurred simultaneously for hundreds of thousands of years.

Rector, an anthropologist at Virginia Commonwealth University, often does field work in Africa, and keeps her fossils in the Ethiopian museum facility. She reconstructs the context in which our ancient family members evolved by studying the animals surrounding them. “I ask myself what hominids might have seen in the area where they slept,” she said. “What did they see when they woke up, what was going to eat them, where did they run to get away?”

Around 3 million years ago, Rector said the climate appears to have warmed slightly. Some of the forests likely gave way to grasslands. But the environment, as a whole, was as mosaic as it is today in Ethiopia. Australopithecus specimens have been found around everything from woodland creatures, to grass-grazing ancestors of antelopes and gnus, to ancient hippos, crocodiles, and fish.

Back then, the sinking lowlands of the Eastern Rift Valley would still have been rather flat, and fed by rivers flowing down from the mountains, and the occasional land-locked lake. Walls of grey, silica-rich boulders, which formed as molten lava cooled, would have been younger than they are today, less worn by wind and rain. Ashen black mounds—created as magma ejects out of vents in the Earth—would have existed also, but their location would have been different. Those seen today along the southwest corner of the Afar Depression, where three tectonic plates collide, have formed within the past several hundred years. Within a day or three, Lucy might have walked past smoldering volcanoes on this dynamic landscape, grazed on berries growing beside crocodile-infested lakes, and into the green highlands, in search of food, mates, or a safe place to rest.

During one afternoon, Lucy might have come across the fresh carcass of an antelope. Famished for a meal beyond insects and roots, she might have paused to examine its succulent flesh. But at less than 4 feet tall, she would have been no match for a pack of hyenas, cackling in the distance. With a mix of hunger and fear, might she have grabbed a sharp stone, and torn chunks of flesh from the beast’s bones that were small enough for her to run to safety with, yet large enough to warrant the risk? After thousands of years of various individuals doing just this, might some of them learned how to bang one rock against another and make their own sharp stones to carry?

To Alemseged, these scenarios are not far-fetched. After all, our cousins, the chimpanzees, stab termites with twigs, and orangutans hold leaves above their head like umbrellas when it rains. But the oldest known stone tools hail from 2.6 million years ago, long after Australopithecus afarensis appears to have gone extinct. Archeologists have long attributed the creation of these tools to our closer kin in the genus Homo.

In 2009, Alemseged realized archeologists might have been searching for stone tools with a biased image in mind. In the museum facility, he pointed to the iPhone on his desk. If you were to look for proof of telephones a century ago, he said, you’d miss them if you expected them to look like this. That year, Alemseged mounted another expedition to Dikika—this time with five jeeps and a team of 50. By then, Alemseged held his current position at the California Academy of Sciences. His team was examining bones from animals in Dikika, searching for signs of action on the land when Australopithecus afarensis walked it. Punctures in the bones revealed that crocodiles had been voracious, and cracks whispered of antelope herds. But the causes of other scratches were unclear.

In particular, a rib from a large cow and a thighbone from a small antelope bore marks that experts using electron microscopy identified as different from the rest. A sharpened stone, they said, could account for their width, shape, and angle. And radiometric dating techniques confirmed that the marks had been etched more than 3.39 million years ago, in the time of Australopithecus afarensis. In Nature, Alemseged and his colleagues reported the first signs of butchery.3 According to the paper, the marks are “unambiguous” evidence of stone tool use, 800,000 years earlier than when paleontologists thought it arose. “This is the first technology,” Alemseged said. “It’s the invention of something with the idea that it will serve some future purpose.”

The finding shocked the archeology world. But Alemseged sees no reason why it should. Australopithecus afarensis’ human-like hands, with long, dexterous thumbs and short fingers, would have allowed them to manipulate stones. What’s more, they may have possessed the intelligence to do it. Alemseged’s colleague, Dean Falk, an anthropologist at Florida State University, measures the size and shape of the inside of skulls, to get a sense of what ancient hominid brains looked like. Her preliminary studies on Australopithecus afarensis suggest their brains were relatively advanced compared with apes’ brains, with an expanded area in a front region of the brain called the prefrontal cortex—an area where intentions are processed.

With a higher functioning brain, our ancestors may have had the cognition to create rudimentary technology. The action represents a definitive change in mental processing. “You need a plan, you need the motor skills to do it, you need to keep the task in mind for as long as it takes, and you need the motivation to go to all that work in advance of when you need the tool,” Falk said. “That’s all frontal lobe stuff.”

If individuals had the foresight to make stone tools, they might have also had the ability to teach one another how to do it. The transfer of complicated information among groups could signify another pivotal moment in our evolution, the origin of exceptional “social-cognitive” intelligence: the ability that builds culture among social groups. Other tool-wielding animals, such as orangutans and dolphins, show a degree of social intelligence—but humans are far better at it. When given a battery of social-cognitive tests, such as producing a gesture to retrieve a reward, 2-year-olds outperformed adult chimpanzees and orangutans. The children succeeded in about 74 percent of the trials, twice as often as primates.4

More directly, stone tools gave our ancestors access to protein-rich food, which would have been essential to the growth of hungry, big brains. Although the brain comprises just 2 percent of our body weight, it demands about 20 percent of the energy we expend each day. A bigger brain would have helped hominids build better tools, and pass their knowledge on to pack members, and down through the generations. It’s a speculative chain of events, but the best hypothesis yet. “The emergence of stone tools is a big bang,” Alemeseged said. “The moment you start walking on two legs, the moment you start farming, the moment you domesticate the dog, these are major landmark moments in our history, which made us who we are today.”

However, there’s a lag in this chain of events if stone stool use began with Australopithecus afarensis some 3.4 million years ago. Drastically larger brain sizes didn’t occur until about 2.5 million years ago, in our closest kin in the genus Homo. Shannon McPherron, an archeologist at the Max Plank Institute for Anthropology, who co-authored the report with Alemseged, said the gap might have occurred if various individuals figured out how to use stone tools independently, repeatedly over time, but never passed the knowledge on.

In this scenario, the fidelity of information-transfer improved over hundreds of thousands of years. By the time Homo produced hand axes—oblong stones sculpted into a point, with a base that fits snugly into your palm—they were learning the craft from one another. The consistency in shape and style, as well as in abundance, is interpreted as evidence.

White is not convinced of Alemseged’s early evidence of butchery. He believes crocodiles, not hominid tools, made the marks in the animal bones. Another skeptic is Sileshi Semaw, an Ethiopian archeologist at the National Center for the Investigation of Human Evolution in Spain, who co-discovered the oldest stone tools from 2.6 million years ago. White and his colleagues found signs of butchery from the same period. “Right after 2.6 million years, we have stone tools, cut marks on animal bones, the expansion of cranial capacity, and the emergence of our genus, Homo,” White said. “These things seem to be correlated.”

Alemseged responded to the criticism by suggesting his colleagues may be fighting to keep their stories intact. “The resistance is not based on scientific grounds,” he said. In the museum facility, his team sorts through piles of rocks and bones collected in Dikika, in search of more evidence. His colleague, William Kimbel, director of the Institute of Human Origins at Arizona State University, who works in the region where Lucy was found, is doing the same. With a cadre of young Ethiopian and international students now trained in the new facility, more paleontologists will be scouring Ethiopia than ever before. “Mark my words, we will find stone tools from 3.4 million years ago,” Alemseged said. “I can’t tell you where exactly they will be, but they will be discovered.”

As I discovered during my trip to Ethiopia, the field researchers love to argue. Questioning assumptions as new evidence comes to light is, after all, the sport of science. One afternoon, Alemseged, Asfaw, Suwa, and Kimbel were going at each other over a splinter of hominid skull. Suwa mangled an English idiom in an attempt to describe his objection to Kimbel’s opinion; Asfaw stared at his friend of 30 years apologetically, unable to recall the phrase.

Even in their most acrimonious moments, field researchers form a tight-knit community based on respect for one another’s full-body approach to science. Their colleagues in offices, who run molecular and digital analyses of fossils, may not appreciate the effort that goes into unearthing the fossils in the first place. “They don’t know that the jeep broke down in the desert, and the driver fixed it on his back with an armed guard protecting him, and scorpions beneath him, and he got malaria,” White said. Without field research, we’d still be telling a story about how crouching apes progressed to standing man against an imaginary savannah backdrop. We’d lack the fossils to tell us that elements of humanity began millions of years ago in a mosaic of environments.

As I traveled through Ethiopia with scientists and local guides, dodging thick sheets of rain in Addis Ababa, driving past Chinese manufacturing plants outside the city, and into the Afar, where I was parched, hot, and hungry, I realized just how fragile the scattered remains of our past are. They are constantly under threat by development (as African countries mine and modernize), conflict (as political situations shift), and global warming (as floods and droughts increase in severity). Ironically, our exceptional tool-making skills now threaten to lead us toward eventual demise.

When considering how long the oldest members of our family survived before they went extinct, it’s impossible to not reflect on our species’ fate. “When you realize that you, as an individual, are part of a very long line, you begin to take it personally, you really are afraid to cut off that line,” Alemseged said to me one evening. “But I am not pessimistic because humans are arguably the smartest species. We have the ability to reverse the damage we’ve done, and push things forward.”

Travel for this story was paid for by a grant from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting in Washington D.C.

References

1. Alemseged, Z., et al. A juvenile early hominin skeleton from Dikika, Ethiopia. Nature 443, 296-301 (2006).

2. Science 326, 1-188 (Oct. 2, 2009).

3. McPherron, S.P., et al. Evidence for stone-tool-assisted consumption of animal tissues before 3.39 million years ago at Dikika, Ethiopia. Nature 466, 857-860 (2010).

4. Hermann, E., et al. Humans have evolved specialized skills of social cognition: the cultural intelligence hypothesis. Science 317, 1360-1366 (2007).

This article was originally published in our “Big Bangs” issue in September, 2014, under the title “Digging Through the World’s Oldest Graveyard.”