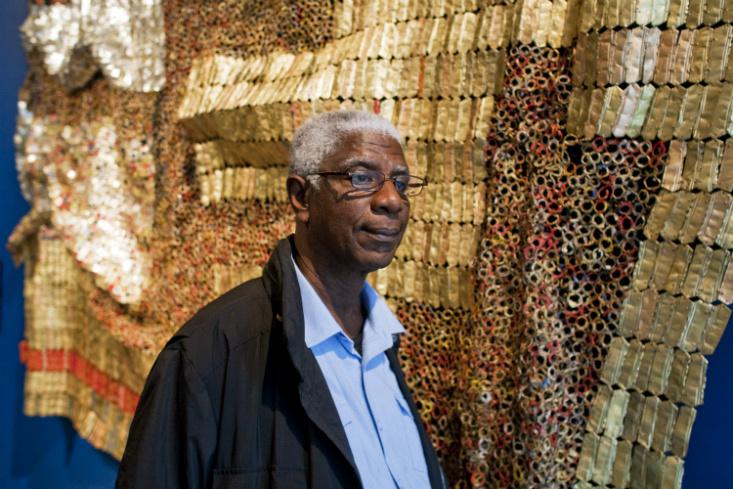

The atmosphere in El Anatsui’s studio is somewhere between a Renaissance artist’s workshop and a recycling plant. The roof is made of thin, uninsulated metal sheets that offer little protection against the hot Nigerian weather. Bags overflowing with bottle tops, bought from local distilleries, are piled all over the floor. Around a dozen young men can be seen cutting, flattening, folding, punching, and tying together pieces of metal into small blocks, which Anatsui tests in different combinations until he is satisfied.

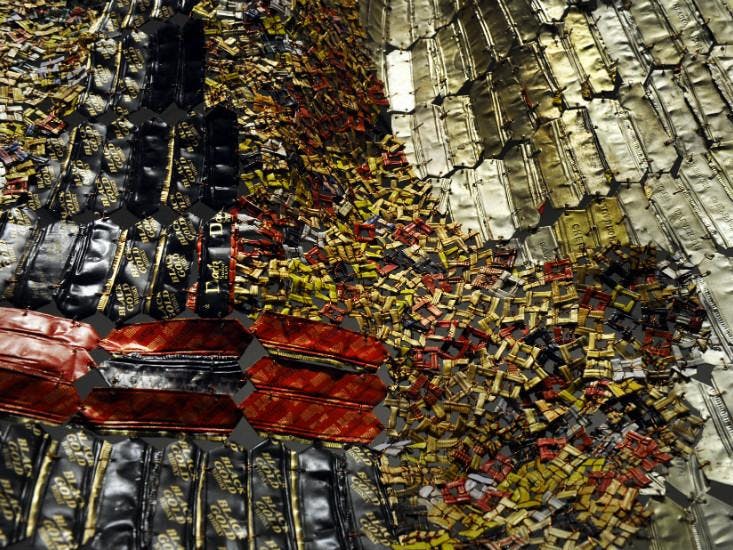

The art made in this studio ends up all over the world. Works are held by MOMA and the Metropolitan Muesum of Art in New York, The Centre Pompidou in Paris, and the British Museum in London, among others. Anatsui, a 69-year-old, Ghanaian-born sculptor, is best known for his large and strikingly beautiful metal hangings, which from a distance, look like folded, wrinkled fabrics. Only on closer inspection is it apparent that they are made up of thousands of squashed bottle tops and neck collars, and that the whole shimmering structure is held together by copper wire.

These sculptures invite viewers to reconsider how we think about waste and our relationship with what we throw away—to look at such items not as junk, but as objects with a long history, which can be extended and reshaped through the act of sculpture. Few of us could name an item of trash we saw on the last street we walked. In asking us simply to look at discarded objects, Anatsui immerses us in the hidden histories and hidden beauties of our environment. As Susan Vogel, an Art History professor at Columbia University, and author of a monograph on the artist has written, Anatsui’s environment-based art is “grounded…in the local, lived milieu, about which the artist [can] speak with authority; and it [encourages] the use of cheap media, in a place where even cement can be expensive.”

In conversation, Anatsui tells me has spent 40 years searching for fresh materials with which to experiment. He sees rich backstories everywhere. For him, bottletops evoke the liquor that Europeans used as currency to acquire slaves during the brutal years of the slave trade—many of whom ended up on sugar plantations in the Americas, sowing and harvesting the crop that would be used to make rum in a kind of vicious circle. He likes materials “that have been subjected to considerable human use: mortars, trays, graters, and tins,” and believes that “artists are better off working with whatever their environment throws up at them.”

The story of how Anatsui began using bottle tops has become legendary in the Nigerian town of Nsukka, where he keeps his studio and teaches at the University. Some villages around the town mark the death of their members by putting together a small monument in the bush made of clay pots. Anatsui had been working with clay pots for some years, and recalls how one day in 1998, when searching in the nearby bush for one of these monuments, he happened across a large bag of colorful bottle tops that had been thrown away. He discovered that more were available from local distilleries, who would reuse the glass bottles and throw away the tops and collar-wrappers.

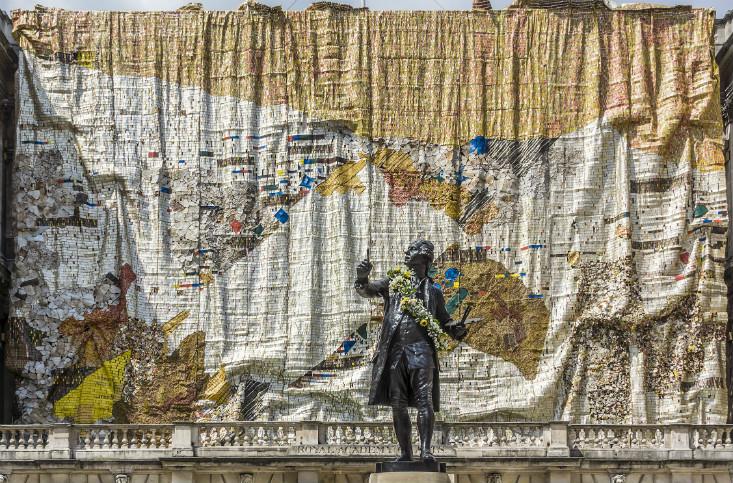

Several months later, Anatsui had the idea of tying the pieces of metal together to create a flexible sculpture. He realized that these “cloths” had an almost textile quality. He has written that the process “was subverting the stereotype of metal as a stiff, rigid medium and rather showing it as a soft, pliable, almost sensuous material capable of attaining immense dimensions and being adapted to specific spaces.”1 After that first experiment, he started purchasing large bags of used bottle tops, competing with the local traders to buy this merchandise. Since 2001, Anatsui has created around 200 wall hangings. From his initial pieces, mainly rectangular and not more than four meters in width, he has added complexity to the shape and increased the size. Some are truly monumental, such as Broken Bridge, a 2012 piece measuring 32 by 10 meters, hung on the façade of the Musée Galliera in Paris.

The result is a body of work rich in contradictions. His sculptures are made from sharp and hard pieces, yet their texture is supple. They are made of discarded materials, but also ones with long, tangled histories, that are imparted with the freshness of newly made art. He acquires his materials in Africa and draws on West African cultural traditions of using and re-using objects for a variety of purposes (religious, ceremonial, or communal); but his found objects have global histories, and his constituency of admirers is global. Ultimately, he asks us to reconsider the borders of the objects that surround us, and to creatively expand what materials can be turned into art.

1) El Anatsui, In the Making: Materials and Process. Michael Stevenson Gallery, Cape Town. (2005)