My roots are in a hilltop village west of Matera, where rabbit and boar run riot in the fields. Figs, apricots, and pears hang in heavy clusters, at eye-level and within easy reach. There, the local girls are famous for their calves, made firm and strong from hauling earthen jugs up steep and stony paths. The weather is as a rule clement, neither too humid nor too arid. The air smells of limes.

I think of it the way I think of the afterlife. It’s an improbable place conjured in equal parts from the gauzy descriptions of my parents and my own wishful longing. The crumpled photograph my father kept in the inner pocket of his leather satchel told me little other than the size of his mustache at the time he was forced to leave the village for good. The shapeless gray forms in the background, which he swore were self-sustaining orchards of peach and black cherry, looked like nothing of the sort. No girls were evident.

I have lived on this rock in the sea since two days after my birth. In all the years since I have not seen any sign of game—an honor of classification I do not confer on the gray, greasy-feathered gulls that sometimes take perch on the higher crags. I have never been to the village near Matera, the one from which my father was exiled with his wife and me, his newborn son, for reasons he never made clear. There was something about a fugitive Austrian soldier, a missing scabbard, a dented helmet, but the pieces have never come together, and by the time I was old enough to press for details my mother would interrupt with a shake of the head and say: Don’t even ask.

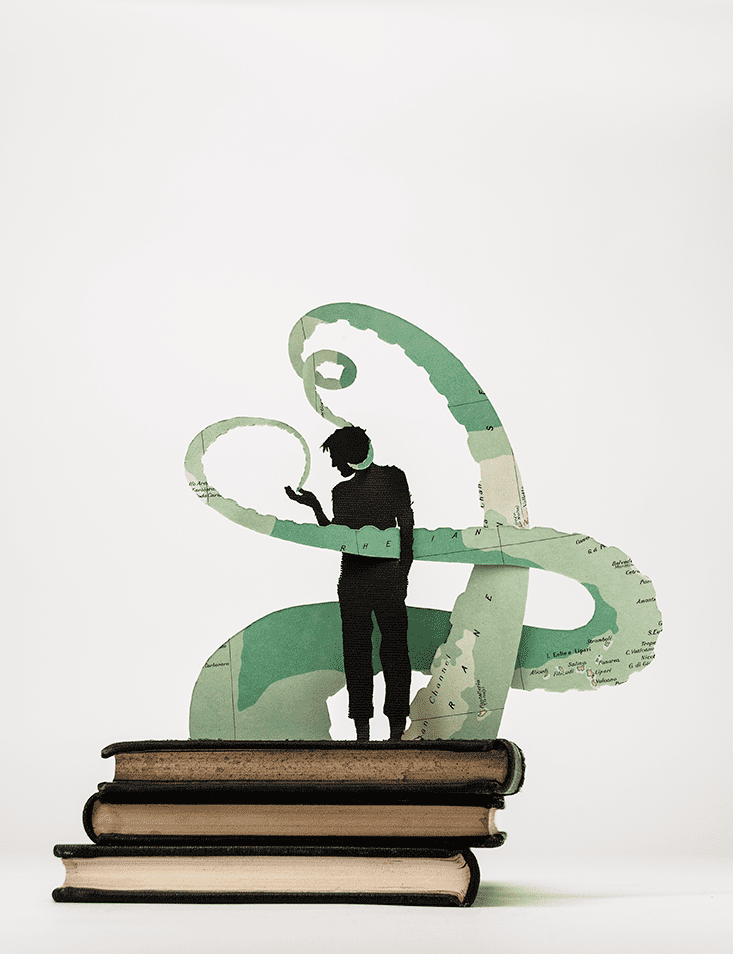

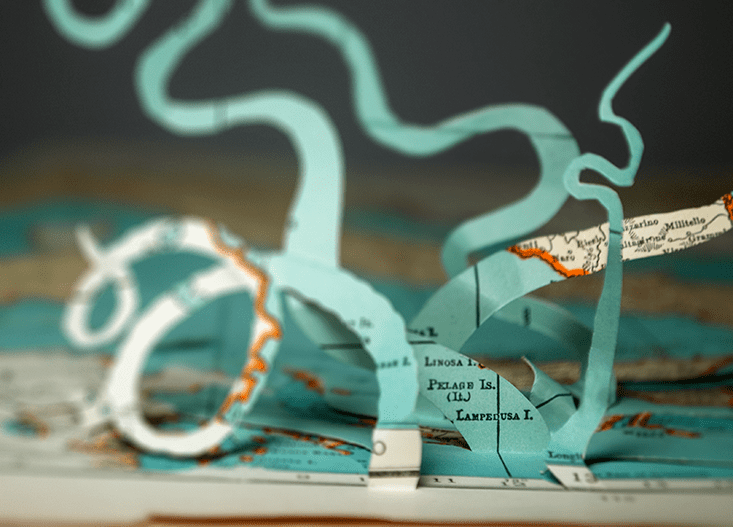

This rock is really two rocks, which are linked by a short natural bridge that twice a day is quietly submerged by the tides and, several times a year, somewhat less gently overtaken by the storm-churned seas. Lampedusa—and I understand there is much to recommend about that island—lies three turbulent hours away by supply boat, a small, steel-sided skiff that brings lemons and whatever fruit might be in season, along with cheese, bottled water, flour, ink, medicine, tobacco, wine, and the occasional newspaper. The skiff leaves with the octopus my wife and I catch in submerged pots arrayed like the beads of a necklace drawn snugly around the island. Octopus fetches an adequate return, and this exchange of goods, this bartering, is how we make our living, such as it is. And as it is, we need nothing more.

“See you in two weeks, God willing!” shouts Pallucci, the short, sunburned captain, as he fires the outboard and guides his dented craft back into the open sea.

I still have my father’s books, his writings, and the crumpled photograph of him. I have the education my mother provided, measured in the painstaking hours she took in teaching me to read, calculate, sing, and sew. I have a wife with whom I still occasionally make love. I’m seventy-two years old, but I know now that I know less than ever of what it would take to live in the world.

My father always implied that others decided his exile, an unjust punishment handed down by petty bureaucrats. Yet, what if he were its sole engineer? What if his exile was self-imposed? In that case, he made me a party to an obsession I had no say in indulging.

At dawn a pair of figures appears on the other rock. They are silhouettes against the eastern sky, only harder, like pillared extensions of the island itself, two stone fingers thrust up from the earth overnight. My wife asks, “Is that a rifle?”

I follow her concerned gaze and spy the barrel of a weapon taking shape above the shoulder of one of the men. It is not like any firearm I have ever seen, but that is saying little. My wife passes me the single-bolt carbine my father brought here with him, its black stock polished smooth from years of handling. It seems to weigh more than the painted wooden boats we drag into the water every day in checking the octopus pots. Surely this mysterious pair must know someone else is here; signs of habitation are all around, from the strung nets on which we dry our meager catch of fish to the pecking chickens that roam freely about—to say nothing of the tricolor Italian flag fluttering atop the rock on our side (my father may have lost his home, but not his patriotism). One of the men now lifts a pair of heavy binoculars to his face, makes a great show of taking in the surrounding sea, then swings back to train them directly on us.

“Fire a warning,” my wife urges.

Before I can answer one way or another, the man lowers the binoculars and raises his right hand high in greeting. There seems to be no hostile intent, and if such a simple gesture seen from this distance can be said to seem friendly, then friendly it is, and I feel I have to accept it as such.

“No,” I answer, knowing my father would have reacted the same way. “Let’s find out why they are here.”

Suffice to say you learn a lot about a woman when you are the only inhabitants of a rock in the sea. My wife is as capable of pulling in pots of octopus as I, and she has never hesitated in sinking her teeth between the eyes of the eight-armed creatures to sever the main nerve to the brain. (The salty, rubbery texture and the sudden pop—like biting into the thick-skinned plums Pallucci sometimes brings, but not quite—have troubled me since youth. Still, this is the quickest and most efficient method of dispatch.) She knows how to read the colors of the sky, and if there’s a pale, pink-orange hue at the southern horizon as the sun sets, she’s quick to haul our three painted boats to higher ground before the thunder sounds. She picks bits of battered shell and crab leg from the wrack of the high-tide line and turns it into chicken feed, a process I liken to alchemy.

After my father died, my mother decided I needed a wife and made the treacherous journey to Malta. “To use the phone,” she answered simply, when I asked why she was going. I was seventeen then, and I knew from her tone that that was all the information I would get. (I knew that she wasn’t lying, either, since no lines had yet been installed in Lampedusa.) Six months later, a boat appeared on the horizon, and as it came closer I could make out two figures aboard. One proved to be a girl, who, from her appearance, I determined was not much younger than I. She had black hair that fell between her shoulders and wide, flat feet that turned out, like paddles, when she walked.

Octopus fetches an adequate return, and this exchange of goods, this bartering, is how we make our living, such as it is. And as it is, we need nothing more.

I found her beautiful, and when my mother confirmed that we were to wed I had no objection. The captain of the tiny boat who’d brought her—an ancestor of Pallucci’s—quickly muttered the vows and declared us married, even as he seemed to be shoving off. Later, my mother—holding a hand-hewn crucifix above our joined heads—blessed us in her church Latin. We hiked to the other rock for our honeymoon, and though the shed in which we spent our first nights has long since been lost to the winds, I will never forget the sight of my new wife’s face bathed in the moonlight that seeped through the window hole, the way she whispered, “Sixteen” when I asked her age, or how we joined ourselves repeatedly in the three days that followed. “Twenty-one times?” I might still ask her, all these decades later, and she will touch her rough, callused hand to the inside of my thigh and correct me with a smile that reveals the only two teeth remaining in her blackened gums: “Twenty-six.”

We would have no children, it soon became apparent, a prospect that seemed to trouble us less than it did my mother. “She’s as barren as this rock!” she said of my wife, regret over the intemperate remark immediately flooding her face. Still, even on her deathbed, the light rapidly leaving her eyes, she managed to extract a promise from me that we would keep trying. And we did. We do.

The newcomers clamber down with a grace that makes me think they have done this kind of thing before. The one in the lead—the one with the binoculars, not the weapon—raises his hand again. His face, flat and broad as a table-top, splits cross-wise in a smile showing many even, white teeth. They look like tiles in his mouth. His skin is slightly freckled as if by the sun, and his hair—like that of the other man—is cut close against the temples.

“Please don’t be afraid,” he says in formal, clear Italian. “We come in peace.”

“I’m not afraid,” I inform him. “We live in peace.”

This gets a laugh, from both of them. My wife looks up at me with a mix of fear and fury. She wears her honor proudly, and she does not like to feel as if we have been belittled.

The men have the kind of clear, colorless eyes that in the books my mother made me read always signaled malevolence of character. Both are clad in smooth-textured black pullovers that fit snugly and are banded at the wrists. On their feet are thick-soled boots whose tops and sides are made of a mesh that looks metallic, silvery, like the sides of Pallucci’s skiff. Each wears a wide-banded watch with a large face—one on his right wrist, the other on his left.

“Signore,” says the one with the binoculars. The smile has yet to leave his face; the other one seems to be evaluating the immediate surroundings. “Please, sir. Do you mind if we take a look around?”

“What for?” My wife’s distrust is instinctive. With her squinting eyes and black mouth, she is suddenly every bit the crone. She rests her hands on her waist and plants her outward-turning feet wide: Just try to pass through me. She must sense something deeply in her bones to be acting in this manner. I try to placate her by placing a fingertip on her wrist, but she will have none of it, and brushes it off.

The one with the weapon speaks. “What for?” he repeats. The momentary amusement he showed earlier has vanished. “What if we say we’re in search of fugitives that you and your husband are hiding on this island?”

“Criminals?” She turns to me. “Hiding?”

“Please,” I whisper. “Calm down.”

“Signora,” the first man says. “Listen to your husband. Why get so upset? We look around a bit, turn a stone or two, and we leave. You’ll never know we’ve been here. Understand, please—” His smile never falters, but is it really a smile? “Understand that our work is serious. These fugitives are dangerous. Not just to you, but to millions of people, all over the world.”

“What do I care about the world?”

“What did I tell you?” the one with the weapon says, turning to his companion. “We’re better off not even asking. If they’re not going to cooperate, then what’s the point in being polite? Their understanding is primitive. The solitude—they’re disconnected from reality.”

“Sir,” I say, interjecting. “We are not disconnected, I assure you. My mother, she educated me. We can read—we read the newspaper a couple of times a month.” I swallow, hoping for my wife’s support, or that the one with the binoculars will understand. “We know about things that are happening. Events. We have visitors—” and here I am thinking of Pallucci, who sometimes brings news of the world—“who tell us.”

“Visitors?” asks the one with the binoculars. His colorless eyes reflect the high clouds. “Maybe, with a look around, we’ll find these ‘visitors.’ What do you say?”

Some years ago we endured a storm unlike any I had ever lived through. My wife and I watched from the shelter of our dwelling as huge silver claws of lightning pulled the night apart, ripping it from top to bottom and side to side. The thunder with its heavy detonations moved closer with each blinding flash, and I thought of all the descriptions I’d read of rolling artillery advancing over the plains. My wife held my hand between hers, and I swear I could feel the tendons and muscles beneath her skin quiver and jump with every concussive blast, as if her nerves were somehow directly attached to whatever dynamo was powering this fury. When the sky finally gave up its burden, the rain it released didn’t fall straight down but came in waves, as if over the bow of a ship plowing through mountainous seas. Rivers formed; we heard the cascading waters in the darkness and wondered whether they might sweep us down the side of the rock and into the ocean. It went on for hours. We didn’t sleep.

“We are not disconnected, I assure you. We read the newspaper a couple of times a month.”

Only at dawn did the tempest subside, and in the weak but growing light we made a preliminary tally of the damage. The chickens had vanished, as had the goat Pallucci had brought us only a month before. My father’s tricolor banner dangled in shreds from its mast. Water still ran in the newly carved channels, carrying silt and gravel and shells and the fragments of any number of the small, ordinary objects that had accumulated since my parents’ long-ago arrival. One of our boats lay in pieces against the rocks, and I surmised it had been dragged from the shore.

“We’re alive,” my wife said, kissing me furiously, her tongue familiar yet somehow mysterious and unknown against mine.

Pallucci reached us later that day, a journey he clearly regretted having made. His face was white with terror: The trailing winds, he told us, had generated waves so high on the open sea that he feared the ocean would swallow him. We located a bottle of wine, and then another. Only after the third did he begin to laugh. He couldn’t go back that night, of course, and he told us later that his absence had sparked less worry than vindication—his relatives had warned him it was too dangerous to go out. “They would rather be proven right than be happy at my survival,” he said. “They’d rather I drown so they could say, ‘See, we told him what would happen.’ ”

We made repairs in due time. We replaced the chickens and goat. I re-stitched the flag. My wife shaped new pots, swept away the sand and grit the storm had deposited in our doorway, replenished the stores of feed. I began to see things with a fresh perspective, telling her that it was like starting anew. Sometimes it’s good to have our lives turned inside out, I said; it helps us see what we have within us.

She rested on her broom a minute, looking out over the water. “I thought,” she said, “that we might die.”

But we didn’t, I told her; look at us now!

She resumed sweeping. “Yes. Maybe. I suppose you are right. But someday one of us will die. You first, me first, it doesn’t matter. And the other will be left alone.”

It was a prospect I’d contemplated, of course, but never did it sadden me as apparently it did her.

“We’ll do it together,” I blurted, “so that neither of us will be left alone.” In that moment I meant it: There clearly could be no other way. I listened then to the rasp of the broom on the stone while a single, dark-gray seagull wheeled overhead. If I thought it strange how talk of a new beginning could so quickly turn to the subject of our inevitable end, I don’t recall.

Yet I do remember thinking this: Wouldn’t it be better for her to go first? If I were to face the facts rationally, to dispense with emotion, wouldn’t this be the preferable development? To be truly alone, if only for a little while, on this blessed isle of beloved solitude. To take the days one at a time, by myself…

I felt closer to my father at that instant than I ever had when he was alive.

The men scatter the chickens and tip the bins of feed. They pull down the rope to which the flapping laundry is pinned. My wife arranges urchins on the single colorful platter she brought with her when she came here—“It reminds me of my birthplace,” she says—and this they knock over too, and when it falls to the ground it cleaves cleanly down the center. A sound like a wave sucked back toward the sea escapes her. The one with the weapon offers a thin smile, then—for good measure and with apparent relish—overturns the table on which the platter had rested.

They work with a grim sort of happiness, seeming to take pleasure not in the destruction itself but its efficiency. The one with the weapon begins to chant something, a barely audible incantation that seems almost religious—though it is perhaps less like a prayer than something self-motivational. The intensity of the chant rises with the speed of his great, sweeping arm, which moves back and forth like a scythe across the shelves of our rough-hewn kitchen and along the mantle beam—reclaimed driftwood shot with the perforations of bore worms—that is mounted above our cooking fire. Down go jars, pots, earthen canisters of salt, and the tiny vials holding the tinctures my wife uses to dye fabric.

“What’s in here?” the one with the binoculars says, stopping beside a curtain hung in a crooked doorframe.

“It is just the bedroom,” I say.

He nods to his companion, who uses the weapon to pull the curtain back. They take a moment to regard what’s revealed—which, I can admit without shame, isn’t much. I could have told them all they’d find: An iron bedstead holding a flat mattress filled with ticking that’s decades old, four flat pillows brown with sweat, a striped blanket so smooth from the nightly turn of our bodies that it’s almost see-through. The crucifix that was my mother’s hangs above the headboard on the stippled, stucco-like wall.

“God bless you,” the one with the binoculars says, “for making so simple a home.” His distaste is unmistakable.

“God,” my wife spits. “How dare you even say ‘God!’ ”

The one with the weapon uses the toe of his strange mesh boot to lift the bed frame. “No trap door? No cellar?”

“Cellar?” I almost have to laugh. “Do you think it possible we could have dug a hole into this rock?”

“Any tunnels?” the one with the binoculars says. “Hide-outs? Spider holes?”

“Spider holes?” I look at my wife.

“Places where you might store things to keep them dry. Places that could serve multiple purposes. Places,” he says, “for a fugitive to hide.”

“Caves,” the one with the weapon adds. He has taken the crucifix from the wall and is running his fingers along its vertical shaft.

“The only cave we know of is underwater half the day,” my wife says, “and a moray eel twice the size of your leg calls it home. You’re more than welcome to look inside it. I’ll even take you there.”

They ignore her. The one with the weapon returns the crucifix to the wall and resumes the strange, wordless chant, which grows louder and more insistent with each syllable.

The other one leans close. He has a distinct smell, an alien odor unknown to this island. His words are for me only. “All we need is a little help. You don’t have to stay here living like this, you know. A little help, and we give you back to the world.”

“If only it were so simple,” I tell him.

Long after my father died, I would ask my mother to tell me the true account of their exile. By this time her memory was failing and her conversation had a way of wandering off into lazy whirlpools of unrelated and unverifiable recollection. I knew that if I wanted to have the facts in my possession, the facts of how this place came to be my home, I needed to collect them from her before it was too late.

Night after night, once the dinner plates were clean and the stars had stretched their blanket across the sky, I tried to steer her back to the hilltop village outside Matera. She cited with maddening consistency the details I already had used to draw my own half-formed picture—the abundance of game, the fruit hanging in clusters, the strong-calved girls, and the air that smelled like limes. The Austrian soldier, the missing scabbard, and the dented helmet all made their requisite but unconnected appearances, and I began to suspect my mother of a willful obstinacy in withholding the vital linking information, as if with eternity in sight it was now more necessary than ever to stick to the story as she and my father had always told it.

One night I finally asked her directly: Was the Austrian soldier my father? And if so, why was it that the man I understood to be my father was the one who was exiled? Or did he do it on his own, choosing to absent himself from the rest of the world?

My wife—having admitted to puzzlement over my sudden interest in a matter she found unworthy of pursuit—made a disapproving noise in her throat and sidled away to make the coffee. I could hear waves gently slapping the base of the rock. My mother chewed on her gums. It wasn’t clear she had heard the question. But just as I was about to ask it again, she began to speak.

“There was an Austrian soldier,” she said.

“Yes?” I leaned forward, detecting something new in her tone, an acquiescence that had not been there before. I would learn it all now.

She turned her gaze to the nighttime sky. She coughed, then ran the back of her hand across her mouth. “A missing scabbard,” she continued. “And a dented helmet.” The last words escaped from her with a stubborn, wheezing sound.

“But,” I persisted, “but was he my father?”

Once more she looked into the nighttime sky, where a small light made steady progress from west to east. “I see those up there from time to time and wonder what guides them. Or what’s in them. Could they see us down here, on this rock? Maybe our cooking fire?”

My wife returned, the clattering espresso pot clattering between her rag-wrapped hands.

“But the soldier,” I persisted.

“He didn’t have to leave,” my mother said.

“Who? The soldier?”

“He didn’t have to stay.”

These riddles were maddening, “Who?” I demanded again.

“That’s enough now,” my wife said, putting the pot before us. She looked at me and shook her head. I watched my mother follow the blinking light—I’m not sure she ever knew of airplanes—until it was no longer visible. Soon we drank our coffee. It was as close as I ever got to learning anything for certain—which is to say, it wasn’t close at all. She may as well have told me, as she did when I was a boy: Don’t even ask.

The strangers are not interested in the underwater cave, once they confirm its inaccessibility. Perhaps, too, my wife’s mention of the moray has dissuaded them. But they explore the rest of the island with relentless attention, bringing me along to turn over rocks or peer into crevices while the one waits alongside with his weapon raised. Much of the morning passes in this fashion. They are meticulous. They are patient, and not easily discouraged. The sun moves higher, and they take off their black pullovers to reveal muscled arms and, beneath tight undershirts, the spread of their torsos. I haven’t seen them eat or drink anything since they came down to accost us all of those hours ago.

“What’s this?” they both demand to know when we reach a small outcropping that becomes visible only after passing behind the opposite rock. Two slabs of roughly the same size lay side by side, the dusty space between invaded by spike-stemmed weeds with flat, serrated leaves. I explain that we are at my parents’ gravesite.

The Austrian soldier, the missing scabbard, and the dented helmet all made their requisite but unconnected appearances, and I began to suspect my mother of a willful obstinacy in withholding the vital linking information.

The one with the binoculars spits what must be a curse in his language. His partner seems unfazed by the sudden lack of composure and lowers the weapon so he can wipe his brow.

“You’re sure you’ve shown us everything?” the one with the binoculars says. When I nod, he kneels on one knee at the foot of my father’s slab, slips a folding knife from an all-but-hidden pocket, and scratches in the dirt beneath the stone. After a minute or so of this, he seems satisfied, although I cannot fathom his intent. He closes the knife, stands, and looks out over the ocean. “Let’s go.”

I’m hustled back to the other rock, where my wife waits. The worried look I see from far away is transformed once more to anger as we approach. The strangers sit us down.

“Listen, the both of you,” says the one with the binoculars. “If you’ve been anything less than truthful, we’ll find out.”

“Know now that we know you’re here,” the other one says.

“What he means is that no one is ever truly alone anymore. Including you. Someone will always be here, or just over the horizon or behind that cloud, which is still close enough to keep an eye on you. You can be sure of that.”

They climb down the side of the rock to where they’ve hidden their craft, knocking over some octopus pots for good measure. My wife shouts a parting shot: “That’s right! Go back to the whores that birthed you!”

I try to hush her, but the strangers don’t respond anyway. The one with the weapon activates the engines—a quiet, medium-pitched hum—and then the vessel races north, trailing a frothy white wake. Before long, they are gone, lost on the vastness of the flat sea. They might not have even been here at all, except, of course—and I can see it in my wife’s tears—they have.

When my mother went to Malta to find this woman who would become my wife, I remained on the rock island alone. She was gone for more than a month, my mother, and in that uniquely solitary time I adhered to the regimen in which I’d been raised, a routine of necessity when one has only oneself on which to rely—for survival and for sanity.

I began my mornings as I always had, as I’d been taught to, by pushing out into the moderate depths of the close sea, hauling in the clay pots I’d lowered twenty-four hours earlier, and returning to shore. Weighted with writhing catch and sloshing seawater, these heavy, homely pots represented not just my labor but the growing body of my good work—the work done daily over the course of a lifetime that was just then beginning to lengthen, like a growing yet flexible muscle. This was the work I wanted to do, the work that resulted in someone, somewhere, having food, the work that becomes good work by dint of sheer, unwavering attention to its completion.

The only thing I added to this routine in my mother’s absence was a trek to my father’s tomb—still just a single slab up there at the time—on the small outcropping hidden by the opposite rock. I can’t say I prayed, exactly, unless handling the increasingly battered photo of him—his mustache eternally dark and thick, the shapeless forms in the background forever giving fruit—can be considered prayerful. Whatever it was, however, it seemed to increase the state of peaceful contemplativeness I’d begun to feel.

“No one is ever truly alone anymore. Including you. Someone will always be here, or just over the horizon or behind that cloud, which is still close enough to keep an eye on you. You can be sure of that.”

At night I’d check the cistern-like tank in which we’d keep the captured octopus until Pallucci came. Once, a couple of anxious, unfruitful days after I’d shipped off my most recent catch with him, there was only one animal in there. He was a big fellow, maybe twenty pounds or so. The pots remained empty for a day or two more, a fact I attributed to the stormy weather to the south, a system that seemed to hug the horizon without getting any closer but that nevertheless spawned waves that churned the immediate depths and sent my prey into hiding. Such spells weren’t unknown to me.

In any event, the big fellow was alone in that stone tank for several nights, and I soon found myself whispering to him as if we were fellow travelers now stranded here, the only survivors of some unidentified apocalypse. After looking in on him I’d replace the lid, a plank of plywood that had washed ashore some months earlier, and then go to bed. In the mornings, however, I began to notice that the bin of shells nearby would be disturbed. At first I assumed it was the seagulls, except that there was never any guano or footprints to suggest their presence. Yet some of the shells—which my mother saved to spread on the paths or convert into some helpful tool or another—would be shattered, or would have a single hole in them as if pierced by a probing beak.

My father always said that the octopus is as smart as any animal that walks on land, and this comment came back to me one evening when I checked on the big fellow. I looked down at him in the clear, cold water of the cistern, then moved the lid back into place. Rather than go to sleep, I decided to stay up and see if what I theorized was happening could in fact be true.

The moon was at its apogee when I heard something rattle. I inched forward. With a noise like someone clearing his throat, the lid began to slide across the stone. In the moonlight I could see one searching arm make an appearance, and then another. Each gray appendage advanced individually, with slow but unstoppable progress. Soon all eight arms had made purchase on the outer edge of the tank, and then the thing hauled itself up, seemed to look around, and, still dripping water, lowered itself to the ground.

I knew octopuses could move across land, but the speed and singleness of purpose that this one exhibited nonetheless came as a surprise. He—and by now I had officially settled on this more specific pronoun—he reached the bin of shells in a matter of seconds, pulled himself up, and dropped himself on top. Now and then I heard a crack as he used his sharp, powerful tooth-like beak to search for any remnants of food. Such strange physical features in this prehistoric animal! But then again, strange maybe only to me. This went on for some time—twenty minutes, maybe more—until he seemed to have satisfied his curiosity. He pulled himself out of the bin, slithered across the stony ground, and returned to the tank. A moment later I watched the plywood lid slide back into place, the grating sound that this produced the only disturbance in the otherwise silent, moonlit night.

I’ve since witnessed an octopus pull a cork from a jug. I saw one sit up and watch the seagulls turning against the sky, as if contemplating flight itself—or maybe the calculating the odds of snatching one from the air. I’ve seen their severed arms set off on their own, wriggling instinctively toward the sea before expiring with an almost audible gasp. I’ve seen them generate new arms, sometimes within minutes. These things once struck me as a kind of miracle, since clearly they are not supposed to happen. But happen they do, and with an inexorability that suggests there is perhaps a lot more going on in the universe than I or anyone else can ever be aware of.

When I see the tears on my wife’s face, I want to tell her about this. It is something I’ve always kept to myself, the story about the octopus. Look, I want to tell her—look at the things we don’t think can happen but do. Look not at what we know but what we don’t. There is probably something else going on, something we might not be able to explain or identify, but something we must allow ourselves to contemplate, even if we don’t know what that thing is. Even if we can’t possibly imagine it, we have to try to imagine it, even when it seems pointless to do so. Look at us—how did we get here, and why are we still here, the two of us alone on these rocks yet in need of no one else? I want to tell her because if it is not voiced then it is not heard, and if it is not heard then it might as well not even be contemplated in the first place.

But I remain silent. There is no such thing as true solitude, my father said, a declaration echoed by the pair of strangers who appeared from nowhere at dawn. But now, having kept this story to myself for so long, I realize there can be, if we allow it to take hold of us. We can put ourselves into exile. My wife silently sets about restoring order. What is going through her head, I cannot say. The rasp of the broom and the grunts of her labor tell me she is present, but she might in fact be on an island of her own.

The morning after I observed the startling journey of that solitary octopus, I gathered his enormous body against my chest. We might have looked like awkward dancers the way we embraced, heads bent back, all of our arms intertwined. He smelled of brine and of the coldness of his species, unchanged over millions of years. I wasted no time in delivering the killing kiss, my teeth piercing the salty outer membrane and snapping the root that made everything inside work. There was a shudder of what seemed like surprise, and then everything was still.

The blood of the octopus is blue, and that was the color of my skin when my mother returned later that day, bringing to an end the only time there was no one to bear witness to this, the fact of my living.

Dominic Preziosi’s fiction, articles, and reviews have appeared widely in such publications as Descant, Front Porch, Smokelong Quarterly, The Saint Ann’s Review, and the Word Riot anthology “What’s Your Exit? A Literary Detour Through New Jersey.” He is the digital editor of Commonweal magazine.