In 2009, more than 47 million computers in the U.S. were ready for “end-of-life management”—so hopelessly outmoded that no reasonable amount of refurbishment could redeem them. Market-driven innovation, thus far hewing to the demanding prediction of Moore’s law, means that every few months, the gadgets in our pockets and on our desktops are pushed closer toward their inevitable demise. Hard drives fail, the erase-write cycle wears out our memory cells, batteries lose their ability to hold a charge, screens crack—and the devices containing these deficient parts are rarely long for this world. Meanwhile, software evolves, bits rot, and file formats shift. Legacy files fail to open themselves up to us on our newer platforms, and new versions of software absorb or crush their predecessors.

Our new media quickly become old. And old in the age of the perpetually new is pretty much the same as dead. That new iPad Air you bought today: Within two years it’ll probably be toast. Sorry.

But if we acknowledge the existence of values other than those defined by the consumer market, we can appreciate that old media are more than just debased commodities, and they have tremendous historical, cultural, aesthetic, and pedagogical value. At a recent event at New York University, Ben Fino-Radin, digital repository manager at the Museum of Modern Art; and Lori Emerson, assistant professor of English and director of the Media Archaeology Lab at the University of Colorado at Boulder, convened ostensibly to discuss “New | Media Archives.” Yet their comments focused instead on the “old”—or, rather, how new technologies and techniques play an integral role in the preservation and appreciation of old technologies, and how the old has much to teach us about the new.

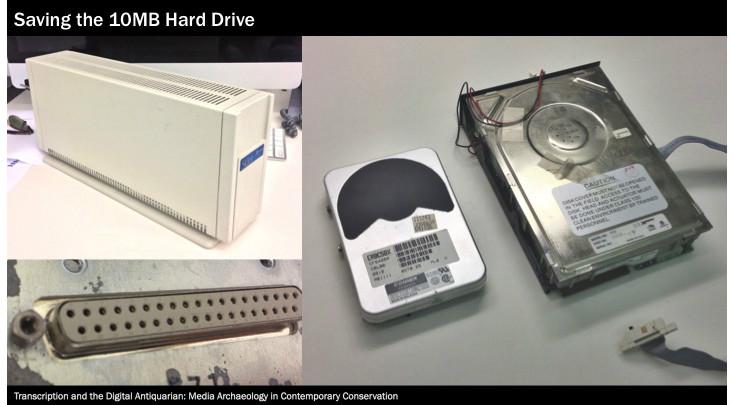

Fino-Radin began with a description of the XFR STN (Transfer Station), an open-door media preservation lab he co-organized at the New Museum, where he used to serve as digital conservator, in Summer 2013. Artists could sign up for three-hour appointments and bring in files of their original work to either the “moving-image station” (which accommodated VHS, U-Matic, Betacam, Hi-8, and MiniDV formats) or “born-digital station” (which handled floppy, Zip, JAZ, and compact disks, and IDE/PATA hard drives, and, interestingly, had much lower demand than the other station) for transfer and recovery. The project put the act of media transfer on display, transforming often highly specialized technical activities into theater; opened the practice up for discussion; and ultimately resulted in the posting of all recovered material to the Internet Archive and documentation of the transfer process.

The antediluvian media came flooding in. Platters rattled, and old ports and cables mated (and sometimes failed to). A particular floppy that stubbornly resisted rewrites had to be disciplined (i.e., erased) via magnet. The museum’s tech team, consulting with other local experts, frequently had to improvise and kludge new and old technologies in order to ensure that participating artists’ files weren’t relegated perpetually to the waste bin. These salvaging transcriptions, Fino-Radin reported, often required an “antiquarian familiarity” with the material properties and operating principles of various formats—as well as an awareness of how new technologies and techniques could aid in the recovery process.

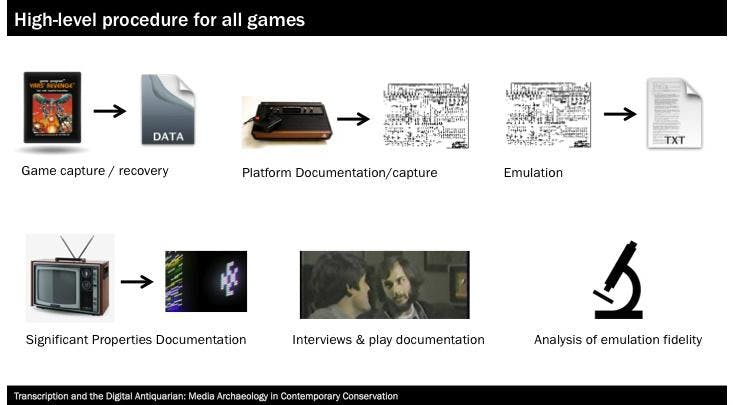

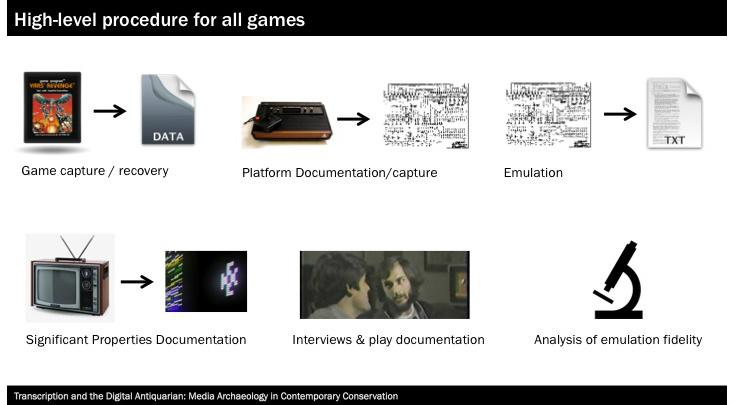

Video games, whose experience is highly embodied and informed greatly by their specific hardware, present a unique preservation challenge. MoMA began acquiring video games—starting with Pac-Man, Tetris, Myst, SimCity 2000, and other classics—in 2012, and they’ve been consulting with various organizations (e.g., the Software Preservation Society, the Maryland Institute for Technology in the Humanities, and Emerson’s Media Archaeology Lab), on best practices for their preservation. MoMA’s efforts operate at multiple levels: They “capture” the game and platform, interview players and rigorously document their experience of the game, and emulate the system on current platforms in such a way that it duplicates the exact behavior of the original.

Emulation, Fino-Radin emphasized, is a methodology—one that requires rigorous documentation and intimate familiarities with the capabilities and limitations of both new and old technologies. Emulation is also, we might say, a means of resuscitation through re-embodiment: keeping alive the spirit of an old game in a new machine.

Yet out in Boulder, Colorado, where the air is a bit drier and conditions for preservation might be somewhat more hospitable, those ancient technological bodies are alive and active. Emerson’s Media Archaeology Lab aims to preserve and provide access to “important works of electronic literature,… along with the platforms they were created on and for; and historically important computer hardware and software, such as the Apple IIe, Apple Lisa, Apple Macintosh, NeXT Cube, and Hypercard.” The MAL, Emerson said, works with what Jussi Parikka and Garnet Hertz call “zombie media,” which are obsolete but still functioning.

Here, old media—which, according to market logic, are outdated, spent, all-but-dead—serve as productive “things to think with.” As at XFR STN, these outmoded technologies offer critical perspectives on our new tools. And as more and more of our lives are lived through high-definition “glowing rectangles,” we need to examine those screens and windows and menus—as well as the poking, swiping, and scrolling gestures we make to activate them—and consider how they structure our interaction, work, sensation, cognition, and creativity.

One way to critically engage with what sociologist Pierre Bourdieu called the “structuring structures” of our lives (and Michael Foucault called the dispositif) is to introduce ourselves to alternatives—including history’s detritus and rejected variants. Rather than effacing the interface, creating a “seamless” experience—as good interaction design is supposedly called to do today—these unfamiliar platforms instead “express the medium,” Emerson argued. She echoed a powerful and resonant call, issued earlier this year, by designer Timo Arnall, for “seamful,” legible, evident interaction that calls attention to human and technological agency and the ideologies of technological development.

We inevitably encounter resistance when attempting to resuscitate the dead or retrieve our discards from the trash bin of history. Fino-Radin recalled hesitance among some creators of software art held in MoMA’s collection, who believe that their work “shouldn’t live forever.” The technology itself often proves intransigent: platters rattle, low-resolution screens strain our eyes, slow processors test our patience. And old interfaces, without skeuomorphic pages and file folders and WYSIWIG programs, often require a cognitive recalibration. In the uncomfortable resistance of the old, we potentially learn to be more proactively resistant to, or at least productively disillusioned by, the new. Perhaps we even come to recognize that those distinctions between new and old, between practicable and wasted, often reflect the market-driven push to buy the latest widget—and that there are other ways of thinking about technological change. We might regard the transfer and recovery efforts of XFR STN and the emulation strategies at MoMA as good ways for examining what the new and the old have to learn from one another.

Our trashed media are still communicating to us—from the basement lab in Boulder, from the 5th floor gallery at the New Museum, and from the e-waste dumps of Africa. We need to be attuned to their signals.

Shannon Mattern, associate professor of media studies at The New School, writes and teaches about media infrastructures, media aesthetics, media art, libraries, archives, and other media spaces. You can find her at wordsinspace.net.