In one important way, grocery stores were very different during my childhood. Catsup was only packaged in glass bottles. Soda came in either aluminum cans or glass bottles, and there was no bottled water—no Fuji, Poland Spring, or Evian. Crackers were wrapped in waxed paper. Everything was bagged in paper. Now, some 30 years later, grocery stores are full of plastic. Nearly every product is plastic-wrapped, then toted away in plastic bags.

Indeed, plastic production and consumption is seemingly ever soaring. Americans disposed of over 40 billion single-use plastic water bottles in 2010, about triple the figure from 2003. Of those billions, only one-third are recycled. The rest, barely biodegradable, stay in our dumps for centuries or wind up in our waterways.

With market experts predicting an enormous growth of plastic use and production in the developing world, it seems there will be no end to the PVC, PET, and polypropylene pile-up.

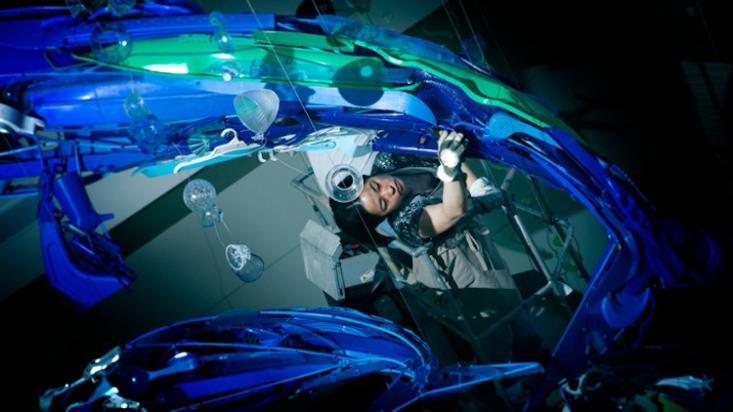

Swept reluctantly along with this landslide, artist Sayaka Ganz converts consumer castoffs into meaningful work. She makes sculptures entirely of second-hand plastics that are in sum much greater than their parts.

“Because plastic objects are quite cheap, people don’t tend to value them, but there’s a lot of thought that went into designing them as well as getting the chemical compound,” Ganz told me in a recent interview.

Ganz created Emergence this past September by fitting together over 1,000 black and white plastic cooking utensils, hangers, and various other thrown-out ephemera.

“When I fit the objects together, it’s like a puzzle to me. When you look at the sculptures up close, because each object doesn’t quite fit, they’re quite small and tied together, and so there is an open surface between each piece,” she says. “I try to align them so that they are all flowing in the same direction to create a sense of harmony. I hope it gives a hopeful message.”

Ganz’s first made her sculptures with scrap metal but made the switch after a trip to a thrift store where she bought a yellow plastic chain.

“I thought, ‘This is just like the metal chains I use,’ and thought maybe plastic would be good to explore. I noticed a lot of kitchen utensils are similar to the shapes I’d already been using, like shovels, garden, and farm equipment. All of the features that make plastic an ideal packaging material make it a good sculpting material.” Plastic is lightweight, cheap, and can be formed into an endless variety of shapes and colors, which explains why it’s used so much by manufacturers and consumers.

Ganz is currently at an artist-residency program in rural Nebraska. In that remote location, there is no trash-pickup service; the residents deal with the garbage themselves. Plastics are collected and taken to a recycling center. Glass is stored in wide, 20-foot-deep silos, and metal is saved for artists to use. The rest is burnt.

Within this process, Ganz has found inspiration.

“Having to live and watch the pile of trash grow has made me so much aware of what we’re putting out in the world…“If I think about it, I get too overwhelmed,” she says. “I am not even not making a dent in the plastic that is thrown out. I would just like to change people’s thinking.”

Indeed, there are signs of a broad plastics backlash. Several cities, including Los Angeles, have banned styrofoam or polystyrene food containers. In 2010, Italy banned the sale of plastic bottles along their UNESCO World Heritage coastline of Cinque Terre, where up to 400,000 plastic bottles were discarded each month. Similarly, the sale of water bottles has been banned in Zion National Park in Utah. Just this January, the town of Concord, Massachusetts, banned single-serving water bottles of 16 ounces or less. In October, San Francisco eliminated the use of plastic bags in stores and restaurants. The city had estimated that it spent 17 cents to handle each discarded bag.

“We have strange relationship with plastic. Many people hate it but they aren’t able to eliminate it from their lives,” she says.

Ganz recently began exploring work with a different kind of hard-to-handle refuse: discarded tires and inner tubes. Her home town of Fort Wayne, Indiana, asked Ganz to create something of the refuse collected from the Maumee River every Earth Day.

At first, I was asked to use metal, but there were very few metal pieces. But the tires, oh my god. There was a pile eight feet high, the size of a one-car garage, and they get that much ever year. Just tires.”

“I feel very sad for [pieces of] plastic, because they’re the orphans of our consumer society. We create them, and then just cast them aside.”

Heather Sparks explores art and science at Science Sparks Art. She studied molecular genetics at The Ohio State University, has a graduate degree in science journalism from New York University, and currently lives in Brooklyn.