Click on the image above for slideshow.

It’s 6:45 on a Tuesday morning as Ulrike, a feisty Berliner in her early 50s whose dyed strawberry blonde hair whispers hints of gray, climbs out of her car, clutching a camera. The September fog is just lifting. Ulrike says she’d be grateful for its cover. We are about to break into an abandoned military hospital built in the 19th century on the outskirts of Berlin. As we approach the sprawling brick sanatorium, Ulrike tells me that our excursion is about more than adventurism and seductive photo opportunities. It’s about being a witness to history, to memory, to ourselves. It’s about the very visceral experience of being in a “lost place.”

We leave the car on a side street and scale a chain-link fence, alighting in a muddy field of grass, out of breath. We climb through a broken, arched window and emerge into the sanatorium’s grandiose atrium. In the empty, silent hall, I feel what Ulrike means. What was once a working hospital, swarming with nurses and doctors tending to wounded soldiers, has lain abandoned for more than 50 years—declared waste, left to wither and rot away. We are witness not just to the passing of time and gradual decay, but to the discarded dreams of a different era, represented in what remains of its opulent architecture. It is a link to the past that feels both distant and immediate.

It’s about being a witness to history, to memory, to ourselves.

Ulrike, who grew up in the former East Germany, shoots photos inside and outside the dilapidated sanatorium. She plans to load the images onto social media sites, where they will be viewed by countless fans who have become enraptured with “ruin porn.” Although photographing abandoned buildings is a rarified hobby, urban explorers, who number about 20,000 globally, have created online forums devoted to the sights of history’s waste and the stories we construct around them. Sigmund Freud said the psychoanalyst acts as an archaeologist, unearthing buried memories. When they surface, the new facts might conflict with the old ones, but they form a new narrative we have to face.

Ruin porn resonates with us today because it is an unmediated experience in a mediated culture. We experience the past directly, not through a book, museum, TV, or newspaper. The old and decayed buildings are not cleaned up or packaged, frozen as time capsules. They poke through the patina of tourism; there are no postcards here. History is present in our minds, stirring our memories. We are alive in the ruins.

Urban exploring is in no way exclusive to Berlin. Yet Berlin exerts a particular draw. It’s a city vibrant with history, one on which war, dictatorship, and division have left their marks. Many of the ruins attracting urban explorers around Berlin are imbued with significance. Old ministries, garrisons, and derelict air raid shelters speak of the historical context under which they came into existence, and under which they were abandoned. Berlin’s ruins open a doorway to a past that stretches beyond the objectified framework of textbook history. Ruins are not just objects of history, they’re palaces of memory. They’re haunted places, full of traces and vague intimations of personal stories that may or may not have happened within their confines. They offer us a subjective point of access to things past, beckoning us to enter and explore.

Vogelsang: History and Memory

Hidden in a dense forest north of Berlin lies the ghost town of Vogelsang, a relict from the Cold War. Like most ruins, Vogelsang comes with a few health warnings—its grounds and meadows remain specked with unexploded mines and grenades. Built in 1951, the military base housed thousands of Soviet troops stationed in Germany. Unknown to the surrounding population—and, in fact, many of the soldiers—its bunkers contained nuclear missiles aimed at London and Paris well into the 1980s. The garrison was abandoned in 1993, a few years after the fall of the Soviet Union. In contrast to many of the ruins around town, Vogelsang has remained relatively unscathed by vandalism. From the Lenin statue at the entrance, the many fading Socialist Realist murals and the odd pair of army boots left by its former inhabitants, it appears to have conserved one particular historical moment. An idea, perhaps. An idea, which from our vantage point looks as pale and dated as the buildings that still enunciate its peculiar aesthetic.

In its present state as a ruin, the garrison reveals the intersection, and perhaps the opposition, of history and memory. Its historical details are clear; the history of the Cold War has been written and rewritten countless times, and with all of that in mind, the curious visitor is perfectly placed to understand the garrison’s historical significance. History, however, is only one mode of grasping what happened. As French 20th-century philosopher Pierre Nora writes, while history looks at the concrete changes wrought by the past, memory lives in the present, for the act of remembering always takes place in the here and now. The work of memory is always continuous, never finished. It consists of smoothing over gaps, of retelling a story—made up of fragmented, disjointed pieces—at any given moment in which we remember.

A walk around the former military base resembles the work of our own memory. The buildings are full of disparate traces of a lost reality; old jackets, boots, and pictures of sweethearts long aged, dead, or forgotten. There are no history books to help us account for those artifacts. Much like the events that form the substance of our own memories, we’re confronted with fragments through which we attempt to form coherent stories and harmonize conflicting pieces of information. Whose wife is that? And what happened to her? Why did he leave his boots and jacket in the gym? Or did another visitor place them there? Where the purpose of history is to create certainty, however illusory, memory is about the stories we tell ourselves—to give meaning to events that, as artifacts of our own lived experience, offer very little in the way of certainty.

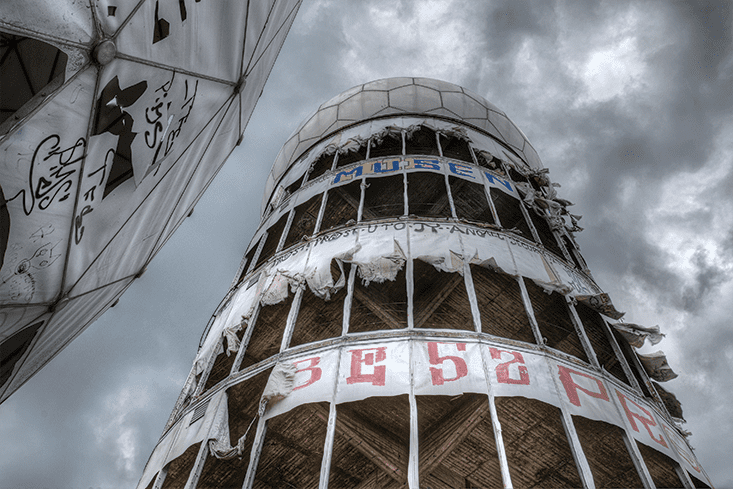

Teufelsberg: Voids and Lapses

Many urban explorers scoff at Teufelsberg, a former listening station for the National Security Agency (NSA) of the United States that sits on Berlin’s highest point of elevation, translated as the “devil’s mountain.” It is a public place that is a popular tourist destination. Everybody and their mother has been there; director David Lynch even made a pitch some years ago to buy what remains of the concrete skeleton holding oversized, golf ball like radar domes whose torn fabric covers rattle deafeningly in the wind. Teufelsberg was built out of the rubble of bombed out buildings and outfitted with listening devices to pick up on signals from east of the Iron Curtain. The first Allied spying activities on the site date back to the late 1950s, though it wasn’t until later that the NSA erected the permanent structure with which the hill has become eponymous. Despite its name, there is nothing particularly hellish about the place. Except, perhaps, that it epitomizes the history of the Cold War, born out of the destruction of the war that went before it. In the early 1990s, the NSA gutted the building, removing all electronics and antennas, leaving only the vast and empty structure that remains on the site and a ghostly presence. In its current state as a ruin—derelict and full of graffiti—the former listening station has much to say about how we remember.

Memory scholar Aleida Assmann distinguishes between two kinds of memory. First, there is memory as ars. That’s the art of remembering, of committing to mind entire books or intricate maps. It’s an art that needs practice to be mastered. As an art, it’s artificial. It’s not the way the mind works when we try to call up the experience of, say, our first kiss or how we felt on 9/11. That is memory as vis, the organic, fragile process of remembrance. Much like a ruin refers to a historical moment, our memories, too, may well reference actual, material events. But they’re by no means an accurate representation of those events. Like these buildings, memories are ruinous—full of holes and lapses. Like the countless and ever-changing graffiti appearing on the walls of the former listening station at Teufelsberg, our memories are subject to constant change, to effacement, to being overwritten every time we call them up.

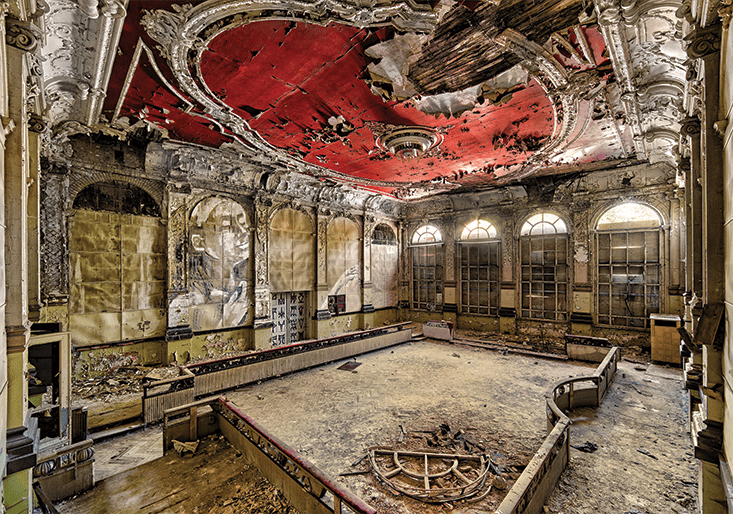

Ballhaus Grünau: The Palimpsest

Just on the outskirts of Berlin lies the once-scenic suburb of Grünau, home to a lush art nouveau ball house that has fallen into disrepair. Ballhaus Grünau—or Ballhaus Riviera, as it was also known—was in use for more than 100 years. From the days of Imperial Germany to the roaring 20s of the Weimar Era, as part of the Nazis’ state-controlled leisure organization “Strength Through Joy” (KdF) and throughout the German Democratic Republic, the ball house stood as a silent witness to the upheavals of the 20th century.

A visit to the ball house reveals little about what it may or may not have seen of grand-scale history; what remains in the space is mostly the chaos of disrepair, the odd faded ornament or mural, as well as the very recent swastika graffiti left by Neo Nazis. The fenced-off ruins attract them because reproducing the symbol is illegal in present-day Germany and the unregulated spaces can accommodate versions of history—such as a glorified view of the Nazi past—that do not square with the current version of collective memory. Their marks add another layer to the disparate elements that make up the dilapidated ball house. There are many such stories, both personal and historical, that must have unfolded and become layered here in the past century. Perhaps, then, the Ballhaus Grünau aspires to the condition of a palimpsest, the ancient parchment scroll continuously inscribed and re-inscribed. It bears no more than fragments of its past inscriptions, which we might be able to discern, though perhaps not decipher. And those fragments may even hint at narratives that sit uncomfortably with us.

Urban explorers, sometimes act as archaeologists of the not-too-distant past. Some spend hours of research preparing for their trips. And no less often do they spend hours trying to piece together bits of information. Countless online forums are devoted to making sense of a place, to unearthing its story—or its many stories—from the rubble, from the layer of debris that obscures it. This work of contemporary archaeology also applies to ruins as representations of how our memory works. They unearth memories buried deep in the realm of forgetting and repression.

Abandoned House: Haunted Memory

The view into someone else’s bedroom is the most sought after type of photograph. All I know about the abandoned house in these pictures is that it is located somewhere in East Germany, no more than an hour’s drive from Berlin. I’m not supposed to know anything else. These places are the best-kept secrets and the most coveted treasures of the urban explorer community; to make their details public amounts to treason. The idea, I’m told, is that flocks of ruin-tourists would descend on them, and disturb their peace. People tend to be more respectful of personal ruins than public ones. They don’t project a historical context as forcefully, and we don’t view them through that lens, in contrast to, say, the garrison or the Teufelsberg listening station. Rather, our access point is entirely through memory—memory that is immediate, personal, and usually oblique. After all, we enter into a private, domestic space. One not too dissimilar to the one we ourselves inhabit and inscribe with our own lived experience.

If undisturbed, abandoned houses seem to halt the passing of time. And this is what constitutes their particular aesthetic: We find ourselves in the moment of rupture—the house in the state the owners left it in when they last closed the door behind them. It is a moment that lasts, suspended forever in the timeless space of the house. The urban explorers I’ve spoken to about visiting such places told me that the feeling is one of “being haunted”; haunted by the former owners’ lasting presence in the space, and the usually inaccessible reasons that made them leave. I think this image of haunting is, incidentally, the most fitting in relating the ruin and memory. Ruins are haunted by the stories, histories, and memories they contain as much as they are haunted by the memories we project into them. So, too, are our own memories haunted. Much of the wealth of our lived experience lies dormant in the depth of our subconscious, waiting to erupt and resurface.

If ruins are waste suspended in time, it seems that time is catching up them. Berlin’s urban explorers are often racing to get to these places before they are claimed by real estate developers, eager to turn them into condos or luxury hotels. What has made the city so special for the past 20 years—its dense condensation of history and memory, with a wealth of places in which this becomes accessible—will soon be glossed over by the ubiquitous glass facades, leaving it indistinguishable from any other modern city.

Luisa Zielinski is a writer living in Berlin, Germany. She completed her MPhil at the University of Cambridge last year with a thesis on the dialectics of memory and space.