One of the most significant effects of the ongoing NSA surveillance scandal is that it drew so much attention to the massive secret, official world that’s grown up in the US since the 9/11 attacks. These clandestine operations have undergone a dramatic recent expansion, though there is of course a long history of clandestine activity in the US government. This part of the bureaucracy puts out a tremendous number of secret documents, and it’s long been known that much of this information is classified out of habit rather than out of necessity.

Many academics, like Columbia University historian Matthew Connelly, would like to be able to access the information that’s hidden by the government but doesn’t really need to be. That’s why he is leading a project called the Declassification Engine, an effort to find out more from documents that are declassified but have significant portions redacted, with words, phrases, and sometimes whole paragraphs blacked out. Considering that the declassified archive includes hundreds of millions of pages, going through them all by hand isn’t a feasible option. So Connelly is working with computer scientists to try to automatically pull useful information from the documents.

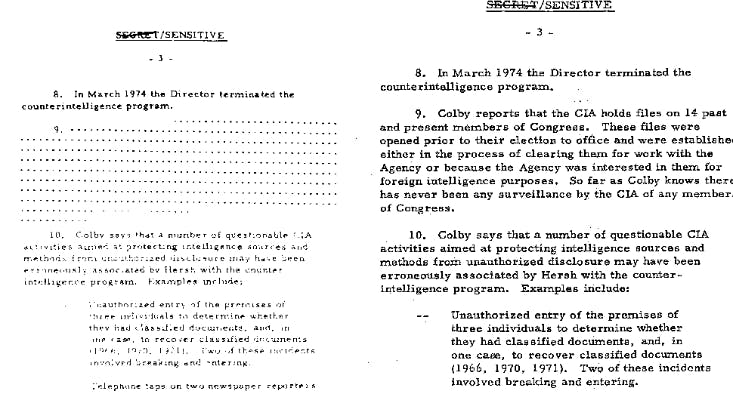

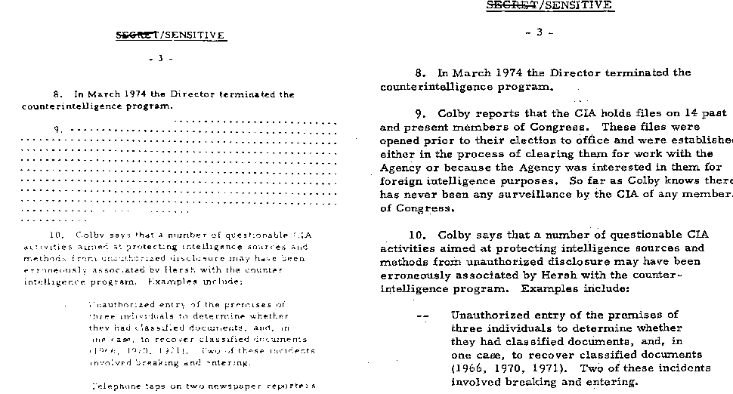

The Declassification Engine relies on a technique called machine learning. Instead of feeding computers a lot of hand-written rules about how they should interpolate the meaning of blacked-out sections, the researchers program the system to ingest a huge pile of documents and draw statistical associations based on the text and the redactions. “We may never completely understand official secrecy,” Connelly says, “but the best solution may be to just throw massive amounts of data at it.” (In the Nautilus article “Math as Myth,” Samuel Arbesman wrote about how this technique makes for far better computer translations than approaches based on programming a computer with a lot of rules of grammar.) For instance, the system can pick up on a document that was declassified multiple times, with different content redacted. In that case it can not only combine the text from different sources but also “learn,” in the sense of statistical associations, what kinds of terms tend to be redacted, which ones are found near redacted sections, etc. Here are two different versions of the same document, released in 1989 and 1998, with different parts redacted:

One of the project’s biggest successes since its launch last year was in unveiling Operation Boulder, a little-known project to monitor people with Arabic names applying for visas to travel to the US. President Nixon instituted the program after the hostage crisis in the 1972 Munich Olympics, though it sounds like something that could be ripped from today’s papers. Most of the overt descriptions of the program are still classified, but the Declassification Engine picked up on the fact that the word “Boulder” showed up in a lot of diplomatic cables at the time, and that it tended be found in ones that had redactions, pointing to its sensitivity.

It’s not surprising to hear that some people in the clandestine parts of the government are not entirely thrilled by the Declassification Engine. Though all of the documents it works on are public, some are concerned “that the collection of declassified documents may have emergent properties, that the whole is somehow greater than the parts,” in the words of Steve Aftergood, a researcher with the Federation of American Scientists. Even some historians, who would love to have revealing secret information, are concerned about what the collected information could say; according to “mosaic theory,” a prominent idea in the intelligence community, a bunch of innocuous facts together could come together to reveal something that could be used to hurt the US. Even the specter of that possibility might make government workers decide to keep documents secret rather than declassify them with redactions.

So the researchers working on the Declassification Engine are walking a fine line—if it’s too good at its job, it might just find itself out of one.

Amos Zeeberg is Nautilus’ digital editor.