About six years ago, I was putting a new roof on a 200-year-old house on an island in Maine when I got a call from Justin Timberlake’s cousin and assistant, a girl named Melissa. I put down my nail gun, told my boss I was taking five, and answered.

I had met Melissa the previous winter, through my best buddy, Antonio. While playing minor league baseball in Southern California, Antonio had started dating Melissa during an offseason he spent in Hollywood. Around Christmas of that year, Antonio sent me pictures of him and Melissa on vacation in Aspen. In several of the photos—riding chairlifts, drinking champagne in hot tubs, making silly faces in the backseat of an SUV—were two people that Antonio now referred to as “Cameron” and “Justin”—as in Diaz, as in Timberlake. Antonio’s connection to such famous people soon became the hot gossip of our hometown, but I, as his best friend, was the first to declare that I could care less. I was 27 at the time, living at home, and working construction while trying to finish my first book—a memoir about the summer I spent as a monk in my mother’s village in Thailand. Hot-tubbing with pop-stars in Aspen was not the eternal stuff of literature.

Later that winter, Antonio brought Melissa home to Maine. I assumed she’d be fake and full of herself, and pretentious—like all celebrities—but her first night in town, Melissa happily got drunk at our local dive bar. The next morning, when I took her on a hike to a remote beach in subzero temperatures—as a test of her fortitude, I guess—she didn’t complain one bit. Like her famous cousin, Melissa came from good people in Tennessee—country blood.

The night before she and Antonio flew back to LA, Melissa gave me a gift: a brand new pair of Nike Air Force Ones, made of red, black, and brown nubuck leather, with little golden tabs on the laces. “You and Justin have the same size feet,” she said. I put the shoes on, imagining that they’d been made in some secret factory under Justin Timberlake’s mansion, staffed by an assembly line of midgets and aging members of ‘N Sync, with Nelly, in a headset, running quality control at the end of a conveyor belt. The shoes fit—perfectly.

Melissa also gave me a Nike sweatsuit that she’d dug out of her cousin’s closet. I tried it on. Apparently, Justin Timberlake and I were also the same height, weight, and build.

“I’m like his half-Asian doppelganger!” I said, a little bit too loudly.

Melissa laughed. Earlier that day, we’d read a newspaper article about Rain, the Korean pop star who the media had dubbed, “The Korean Justin Timberlake.” Because my mom was Asian, I allowed myself the indulgence of punch-lining several jokes with the fundamental American truth that no Asian could ever be famous like Justin Timberlake.

The joke should have ended there, but I couldn’t stop myself. “Hey Melissa!” I said, moonwalking across Antonio’s kitchen while humming “SexyBack”—the hit from Timberlake’s album, FutureSex/LoveSounds, that had spent seven weeks at number one on the Billboard Hot 100. “Tell your cousin to check the weather forecast! Heard that Hollywood’s gonna get some Rain!”

The next morning as I sat down at my desk to write, I felt depressed and uninspired. Antonio and Melissa were back in LA, and I was stuck in boring Maine writing a book about monks.

For the next few months and into the spring, while Justin Timberlake toured around the world singing and dancing in front of sellout stadium crowds, I sarcastically bragged about the origin of my sneakers to people who, I knew, gave less of a damn about Justin Timberlake than I did. But I could feel myself growing slowly jealous of the man who had once owned my sneakers. Every time I turned on the television, I saw his face; every time I turned on a radio, I heard his voice. He hadn’t written a great American novel, he hadn’t marched on Washington, he wasn’t connected to a social movement or any remotely important cause, but he was everywhere. He was branding his own tequila, starring in his own movies, breaking up with Cameron Diaz, appearing at parties for a fee of at least $1 million. I could not ignore it: He was in my head, in my ears, and on my feet.

That June, Antonio told me that Melissa had told him that Justin had told her that he’d been thinking of writing a book about his life. My memoir was just a few months from publication at the time, and Antonio had joked with Melissa that she should pass my name on to Justin as a potential collaborator. Melissa liked the idea, and said that she would. I pretended to take an ironic pleasure in the possibility of collaborating with a guy with whom I had nothing in common—hey, a guy who writes about monks is writing a book about a famous pop-star! funny!—but for the next few days, every time my phone rang my heart beat a little bit faster and I said a brief and silent prayer. By July, my hope had diminished. By August, I signed on for a construction job to make up for the months I’d spent writing my book. So, back to the roof:

Who’s your agent?” Melissa asked me. Behind her, the low and angry voice of a fat perspiring rich man barked the same question, and then barked it again.

I told Melissa the name of the man who, I didn’t think, gave a damn about me. My book deal had fetched me ten grand—a sum that fetched my agent just enough money to take an A-list client out to lunch.

Melissa repeated the name to the low and angry voice of the fat perspiring rich man and then said, “Can you be in Boston in four hours?” She explained that Justin had a show that night at the Boston Garden, and it might be an opportunity to meet him, and talk to him about the book project. The show started at 8 p.m. She was going to leave me a free ticket.

I could not ignore it: He was in my head, in my ears, and on my feet.

I did the math. There was no way I could get off the island, get home, shower, change, and then drive three hours south to Boston without being very late. I also had dinner plans with my girlfriend, who had already put me on her permanent shit list because I was always broke, living with my mother, and more interested in my desperate writing career than our relationship.

“I’ll be there,” I said.

Back on the roof, my boss—a 6-foot-2, 250-pound former hockey goalie—asked me what the call was about. On the mainland, our conversations were only about tools, building materials, and women. The isolation of working on an island all day, however, lulled us into an effusive bro-intimacy. I talked to him about writing, he told me about his depression. It was weird.

“I’ve got a chance to write a book for Justin Timberlake,” I said. “It could change everything.”

“You and Mr. Sexy Back?” my boss said, lifting a bundle of shingles with one hand off a section of staging. He looked at his watch then reached for the nail gun. I handed it to him solemnly. “I’ll finish up on my own,” he said. “You just get going.”

I unclipped my tool belt, climbed down from the roof, and hitched into town just in time to catch the afternoon ferry back to the mainland.

At home, as I scrambled to get out the door, I contemplated a series of unanswerable existential questions: Why should one person be so worthy of my sacrifice? Am I manipulating my self-created values to justify my desire to be in His presence? Does it make me less of a man to get excited about watching another man dance upon a stage? And finally: What should I wear?

I showered, then tried on several variations of jeans and T-shirts. I put some kind of gel in my hair then rinsed it out. Then I put on the same clothes I’d been working in that morning: black Carhartt jeans and a T-shirt. Then I put on his sneakers, stared at my feet for a few minutes, took them off, and put my work boots back on.

On my way out of town, I stopped by my girlfriend’s house and explained the situation. “What?” she said. She’d grown up in Maine, too; she knew what kind of man I was, and she knew what kind of man she wanted to be with. Getting ditched for Eminem, Snoop, Ice Cube—maybe. But Justin Timberlake? “You really want to do this?” she said, her face wearing an expression that really said, “Take me with you or else I’ll hold this against you forever.”

She was so pretty in the dusk light, but I felt doors closing, slamming shut, others opening. “I’m going,” I said, showing an uncharacteristic degree of balls. “I’ve got to do this on my own. It’s my job.” As I pulled out of the driveway, she laughed at me.

I went about 90 down I-95 in my black Toyota Tacoma—a truck I’d bought with my measly book advance because it reminded me of a powerful black war horse or maybe just a giant four-wheel-drive penis. I blasted the radio while white-knuckling through tourist traffic, a pinch of chewing tobacco in my cheek, my mind nic-buzzing with interjections: You’re such a pussy! You’re not a pussy! You’re a sellout! You’re not a sellout! You’re going to be famous! This won’t amount to shit! You’re deceiving yourself! No you’re not! What if he kisses you? Will you kiss him back? Is that cheating? Why are you thinking that? You’re going to be famous! Three hours later, I was crossing that big birdlike bridge over the Charles: the river a mote, the Boston skyline a kingdom to which I, a peasant, had been given a free pass.

It was almost nine by the time I’d parked and found my way to The Garden. Then I was riding up a series of escalators; then I was running down a dark hallway; then a pair of metal doors were opening and I found myself on the ground floor of some weird thumping universe, in the middle of which, upon an enormous rotating stage, was a small blond man in a gray suit vest and tie, singing and dancing atop a black piano, his face amplified upon a gallery of massive screens to several thousand times its size. Surrounding the little man were a dozen black musicians, and a ring of multi-ethnic dancers. I took a seat on a stool just a few feet from the stage, next to a crying teenage girl.

For the next four hours, I watched Justin Timberlake sing and dance and move with a confusing blend of envy, love, admiration, and disdain. On stage, it was clear that he was working at least as hard as I had earlier that day on the roof. It was mid-August. In the last eight months, he’d performed in more than 30 cities across America. In the last three days, he’d performed in his hometown of Memphis, and in Atlanta. His tour would not stop until a final show at The Staples Center in LA, in mid-September.

The Marlboro cowboy sitting at his humble fire was no longer the object of female lust; now, the preferable male archetype wore white three-piece suits and Sinatra-style fedoras and sang falsetto.

The show that night had the methodical flamboyance of a Broadway musical, the vivid grandeur of an Evangelical church service. When he wasn’t gliding across the revolving stage, he was sitting at the grand piano, or playing a guitar, or changing his outfit. In some vague proclamation of musical and cultural chameleon-icity, he bounced between the rings of his musicians and his dancers, flirting with them, sliding into perfect step as they marched right and left. When he sang, The Twenty Thousand sang with him, or chanted his lyrics exactly when he told them to. When he told The Twenty Thousand to clap, they did, with perfect rhythm. When he told them to wave their arms, they did, all at once and up and down. Toward the end of the show, when he performed the snappy and improbable breakup anthem, “Cry Me a River,” The Twenty Thousand hated the then train-wrecked and Predator-headed Britney Spears; when he finished the song with a half-cover of Lionel Richie’s “Easy Like Sunday Morning,” they found it in their twenty thousand hearts to forgive her. I forgave her, too.

He—his voice, his music, his moves, his amplified being—had convinced city girls and country girls to wear less clothing and convulse in bars and clubs and in living rooms and in the passenger seats of their boyfriends’ cars. And because of this contribution to the sex life of millions of young American men, he had complicated the vision of what it meant to be a man: The Marlboro cowboy sitting at his humble fire was no longer the object of female lust; now, the preferable male archetype wore white three-piece suits and Sinatra-style fedoras and sang falsetto.

When Timberlake reached out to his crowd, they reached back, desperately and hungrily. When he said anything at all, they screamed. Toward the end of the show, he paused between songs, his voice so rife with authenticity and earnestness that it melted the aura of divinity that had, for the last three hours, rose up around him like a fog. “I wake up every morning,” he said, “and I think to myself: This is what I do with my life, this is my work.” The crowd fell silent. His enormous face had grown sullen and thoughtful. “I want to thank you for making my dream come true,” he said. “Really, I’m so grateful to be here.” Then he held a test-tube to his lips and said, “Let’s take a shot!” and the crowd erupted. The teenage girl sitting next to me was still crying.

Shortly after Timberlake’s naked confession, a famous blond actress who I had fallen in love with during several of her average movies made her way toward the stage. Dressed in a bright white tunic, she descended several sections of stairs as if riding a hover-board. Ghostly, thin, she walked with the nonchalance of a teenage girl soon to be damaged by her beauty. With her entourage hunched behind her, the blond drifted through the crowd, past several security guards and roped off VIP sections, as if the stage-side chaos was merely a busy downtown crossing. I watched her until she vanished into the shadows. But my last memory of the show occurred when Timberlake circled the stage, reached out to the darkness then crossed the section of stage directly in front of me. He reached out to the teenage girl. Without meaning to, I reached back. He looked at me, and paused, then pulled his hand away, and every time I reinvent this moment in my memory, his face morphs into mine.

Outside The Garden, in the summer night, two young black men sitting on the curb drummed sticks against plastic buckets while drunk blond girls who’d been at the show danced in front of a crowd. I watched the boys for a while, chewing on some big idea that I could not put into words. Then I went into the parking garage where I had parked my truck and waited to hear from Melissa.

For the last half hour, Melissa had been texting me with vague updates from backstage: First it was going to be ten minutes, at some bar in town; then it was half an hour, somewhere else; then there was nothing. Around midnight, I lay down on the bench of my truck and fell asleep. About 12:30, I woke to the beep of another message: ritz bar. avery street. room 1248.

I had no idea how to get to The Ritz. I drove the wrong way down a one-way street. I got lost in a parking lot. I finally asked a cop for directions. When I pulled up in front of The Ritz, a valet came to my window. I had never used a valet service before. I gave him my keys, watched my truck disappear into the doom of a garage door. Then I walked through the front entrance of The Ritz. A man in a suit came toward me swiftly and asked me if I needed help.

I almost turned around to leave. Then I said, “Room 1248.”

The man looked at me and blinked. “Certainly,” he said, gesturing toward the elevator.

Then I got another message from Melissa: Meet us at the bar.

“I’ll be meeting them at the bar,” I said to the man.

The man bowed, gracefully opened his arms in the direction of the barroom, let me pass.

The Ritz barroom was dimly lit and elegantly subdued. Couples sat at small tables sipping cocktails and discussing uncontroversial topics. I took a seat at the bar. The bartender asked me what I wanted. From high upon a neon-lit shelf I ordered the most expensive scotch I could pronounce—a Laphroaig. Then I changed my mind. “A Jameson,” I said. The drink cost $16. As I waited, my breath became short. To kill the feeling, I finished my drink. Several minutes passed. Then the air shifted. Something invisible churned. The low light of the mid-ceiling thrummed with a dark, menacing electricity. I spun around in my stool.

The famous blond came first: all shoulders and hair and skin. I felt as if I were in her movie. She was followed by an entourage, which included her traveling personal trainer, a preppy androgynous woman wearing a plaid shirt and a suit vest and a bowtie, and a perfectly attractive brunette in a puffy down vest. Melissa came next. She was followed by her high school pal, a representative for Timberlake’s clothing line William Rast. Behind the five girls, and not much taller or broader or more striking than any of them, came Melissa’s cousin.

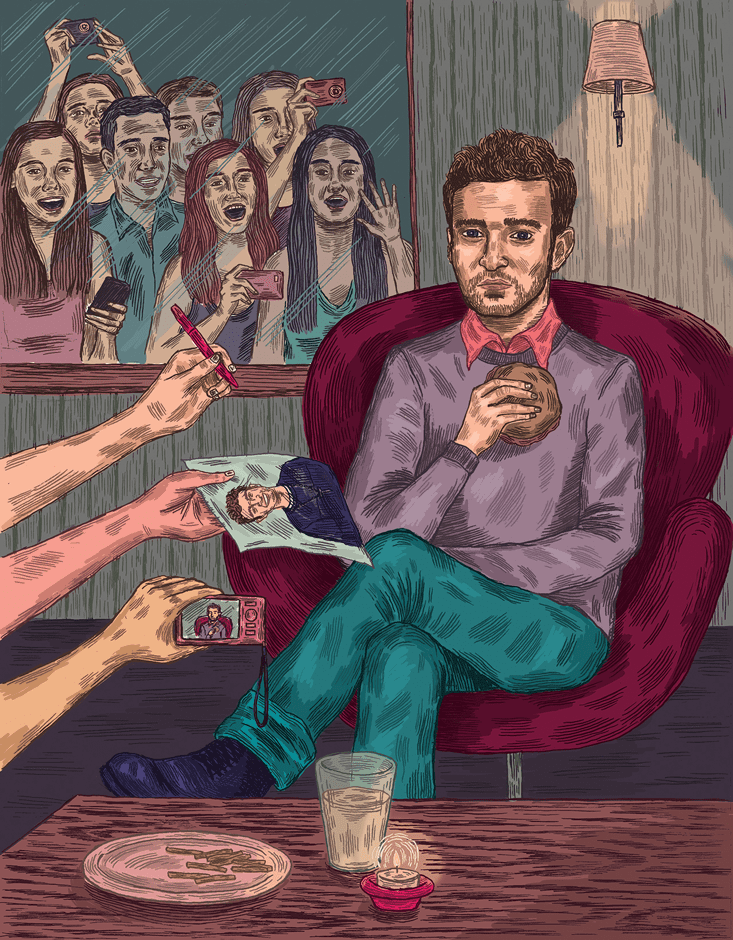

He did not enter the room with any emanation or dazzle or poise. If I hadn’t seen him on stage two hours earlier, I might have guessed he was one of the women’s tag-along kid-brother. Wearing jeans, white sneakers, and a carefully weathered sweatshirt, he scanned the barroom suspiciously, his face anxious and twitchy, as if at any moment The Twenty Thousand might erupt from a hidden closet, descend upon him from the ceiling.

I joined the group in a dark and somewhat concealed corner, at couches and a small table. Melissa hugged me. Then the blond stood and offered her hand. “Hi,” she said, “My name is The Fading but Still Very Famous Blond Actress.” In her introduction was the perfect expression of her art: to garnish her famousness with a humble dash of almost-famousness.

I met the other girls, who would all soon forget me. Hunched into the corner of the couch, he was looking at me with a face like that of a thief on the run. His arms were folded over his chest and his hands were hidden in his armpits. “Wasup, man,” he said plainly, and then to no one in particular, “I’m freakin’ starving.”

Melissa called over a waiter. Everyone ordered a mixed drink—martinis with the best vodka, top shelf-scotch and soda, expensive gin and tonic. I ordered another $16 whiskey.

“A ginger ale,” he said. “And you got anything to eat?” The waiter gave him a menu. He studied it for a moment. “A chicken sandwich. Please.” The waiter nodded, but before he left, Timberlake said, “Could I get some fries with that, too?” And then, “Maybe you got somethin’ to eat while we’re waiting? Like some nuts or pretzels or somethin’?”

The waiter brought out the mixed drinks and the ginger ale. When the chicken sandwich and fries arrived, the people came, too. The first was a middle-aged round woman in a trench coat with big dyed hair and bright red lipstick. “I think you’re amazing,” the woman said. “I just think you’re so talented.”

Timberlake looked at the woman, perhaps several degrees beyond her, his mouth full of chicken sandwich. “Thank you,” he said.

“Could I take a picture with you?” said the woman.

Timberlake stopped chewing. His forehead wrinkled.

“He’s eating, ma’am,” Melissa said.

The woman didn’t move.

“I’m sorry,” Timberlake said. “Not a good time. I’m eating.”

“Please?” said the woman.

Timberlake smiled but remained silent. The woman walked away. He shook his head. “Sometimes I just want to spit my food at them.” He looked at me for agreement, realized he didn’t know who I was then looked at Melissa. “I mean that’s really rude of me, right? That I wanted to spit my chicken sandwich in that woman’s face?” He exhaled. “I’m sorry,” he said. “But sometimes I just want to eat my damn sandwich.”

Another woman came up and asked for a picture. Timberlake’s jaw, mid-bite, tightened.

“I’m sorry. I’m eating right now,” he said.

The woman defended herself with a comment about her teenage daughter and her teenage daughter’s friends. Timberlake smiled and nodded and told her thank you but not now. The woman, silent, stayed where she was. Timberlake turned away from her, and continued to chew.

“Ma’am,” said Melissa. “We’re eating.”

The woman walked away.

“That’s ridiculous,” Timberlake said. “Why would anyone want to be the whoever of wherever?”

Several minutes later, several faces appeared in the windows of the barroom like small moons. The faces were all Asian. They were heading down Avery Street, back to Chinatown, I guess. For a moment I considered going with them. There was a joke to be made but I couldn’t think of it. A man in a Ritz blue blazer walked outside and ushered the faces away. By then, Timberlake’s french fries had wilted, and the chicken in his sandwich had probably cooled by a few dozen degrees.

Then a large well-liquored man in his 50s approached the table with a drink in his hand. I had a heavy feeling that something newsworthy might happen. Nuts and pretzels were going to fly; someone was going to throw a shoe. The large man moved forward, without a drop of self-awareness or inhibition, and said, “Hey Buddy!”

Timberlake turned.

“Hey, I don’t know shit about your music, but I just want to say: Dick in a Box! That’s funny shit!” The man held out his hand for a high five.

Though the first of Timberlake’s SNL shorts had aired the previous December, its enduring social frequency had recently knocked Borat’s “Very Nice!” from the top spot on Billboard 100’s Most Poorly Imitated Material.

Timberlake paused. He contemplated the table in front of him. He ate a fry. Then he rose, calmly, and looked the man in the eye. I had seen that face before: twenty thousand times bigger, upon a massive screen, sweat upon its forehead, a singing mouth. “Hey, thanks a lot,” he said, and met the man’s palm with his own.

“Keep up the good work!” the man said. “Dick in a Box! I mean it! That’s funny shit!”

Timberlake sat down and took another bite of his chicken sandwich. Then he looked at me, perhaps forgetting that I was in the process of listening to every word he said. I looked back.

“That dude was pretty funny,” he said.

“Yeah,” I said while trying to think of some way to express that I was more than just another person who wanted to take something from him.

At some point in the evening, not long after last call, the barroom was cleared out—because, I think, we were there—and our table was assigned a personal afterhours waiter. He was a handsome and comfortable Latino man in his 60s, wearing a bow-tie and a vest. As the blond and her crew ordered more drinks, Timberlake continued with ginger ales. The blond asked the man where he was from. “I come from Brazil!” he said, to which the brunette responded, “I’ve been to Brazil!” When the waiter asked her what she was doing there, a confused and empty silence fell upon her. “I was just hanging out,” she said. At some point during this conversation, Timberlake had moved to the bar to sit by himself, and was now speaking to the bartender inaudibly, but with a very sincere face.

The after hours of the Ritz barroom seemed reserved for Hollywood members only. At some point, a former Beach Boy—I can’t remember which one—walked past our table. He put his hand on Timberlake’s shoulder as if he was his father, said something important, then continued on. Then the actor Jason Biggs arrived by himself, looking as though he’d gotten off the elevator on the wrong floor. He was wearing a yellow down vest, cargo shorts, running shoes, and a visor, and he carried a small white poodle under his arm. He and Timberlake exchanged a falsely rehearsed snap-pound combo handshake and then Biggs gestured to the blond actress like he’d seen her earlier that morning. “Oh! Hey!” she said, as if they really had. Then Biggs said, “I’m beat,” and he and his poodle wandered back toward the elevator.

Avery Street was finally dead enough for the most famous young man in the world to stand outside his hotel and smoke a cigarette with a less famous actress who bored him.

It was roughly here that the night began to age. After a brief rendition of The Running Man, the blond faded, and the only remaining entertainment was supplied by her androgynous friend, who, now tipsy, stood up and country-danced to a jumpy R&B track. She had her thumbs hooked into her belt loops; she bopped her head to the beat as if to parody a shy, intoxicated, secretly gay cowboy in a dive bar. It was funny. From his seat at the bar stool, Timberlake laughed. Melissa, knowing that I wasn’t here just to hang out, tried to bring me to his attention.

“So how’s your book coming?” she said. She looked at Timberlake and whispered something into his ear. I heard her tell him a number of other things: that I had once held the middleweight title of a barroom boxing show in Alaska, that I had hitchhiked across the country, that I had paddled a sea-kayak from Washington State to Alaska. I watched Timberlake’s face, waiting for his eyes to light up, to tell me that I was the one to tell his story, that he would give me a small portion of whatever he had that everyone wanted a part of. Then, he flinched. “You were a monk?” he said. His face turned brooding, and suspicious—not of me I don’t think, but of the very notion of monasticism. “What do you have to do…to be a monk?”

I thought about that, the complexity of my story—ethnicity, religion, heritage—unraveling at my feet. “You have to shave off all your hair and your eyebrows and wear orange robes,” I told him.

Timberlake squinted. He wasn’t really listening to me. “Wait,” he said. “I don’t get it. Can anyone just go be a monk?”

“Sure,” I said. “You could go to the village where my family is from, and you just say you know me, and I bet they’d take you in.”

By now, all the girls had moved on to the next thing. The blond was yawning.

“What’s that like?” said Timberlake. “When they shave off your hair and eyebrows?”

“It’s weird,” I said, “because all these people from the village are watching you and the one who does it is an old monk and he uses a really big razor. It’s a very strange feeling. I didn’t know how to react. I just…”

Timberlake interrupted me. “Man, if I had to sit there and let someone do that to me…I think if I had to sit there and in front of all those people while the old monk was shaving off my hair,” Timberlake’s eyes got bigger, “I don’t know, man. I’d probably freak out, too. I’d probably come out swinging.” Now he was staring at the dark carpet as if it were a thousand miles beneath him. By the look on his face, I could tell that he’d really brought himself there: Justin Timberlake was wearing robes, Justin Timberlake was hairless, Justin Timberlake was walking barefoot along a brown canal, Justin Timberlake was celibate. “Yeah,” he said. “That would make me crazy. I’d probably start looking for someone to hit.” He looked at me intensely and didn’t look away; I nodded, as if I understood exactly what was on his mind.

That night, I slept on a couch in Timberlake’s many-bedroom suite. I wasn’t sure if he was sleeping in the suite also, but across the hallway was a shut door. Before I lay down, I put my ear to the door, but didn’t hear any sound. Even though the tabloids had confirmed that he and Cameron Diaz were no longer together, I still couldn’t find it in myself to care that much if the famous blond actress was in there too.

It was not yet sunrise when I woke to the feeling of a warm body at my feet. The dark form sighed heavily. I had to blink before I could figure out who it was: a dog—a boxer, actually. There was another one in the corner. I thought: Since when did the Ritz-Carlton let dogs stay over in their luxury suites? I reminded myself whose room I was in. Of course the dogs could stay.

Then I felt an urge to breathe real air. I laced up my boots, crept past the dogs, past the closed door, and into the hallway, and took the elevator downstairs.

It still felt like night as I walked through the empty lobby of The Ritz, down Avery Street, toward Chinatown. Old men swept dust from storefronts into the gutters; grocers laid foam-wrapped fruit upon wooden tables. In a park next to the red and golden gates of the neighborhood, I sat on a bench and watched old people exercise. A man slapped his cheeks. Another man waved his arms in circles. A woman lifted her shoe over her head as if it were a barbell. As I watched her, she became a gonging oriental metaphor that suggested something about the weight of a soul, the worth of a person, the value that the world assigns to each of us, despite the fact that we all arrive the same way and that some of us get paid $1 million to show up at someone else’s party.

I slowly recalled how the night had ended: At some point, the conversation about being a monk in Thailand had turned into a conversation about the possibility of Timberlake touring in Asia. It was then that Melissa cited the article we’d read when she and Antonio had last been in Maine—the one about the Korean pop-star who called himself Rain. She recalled how Rain was now known as “The Korean Justin Timberlake.”

“That’s ridiculous,” Timberlake said from the bar. “Why would anyone want to do that? Why would anyone want to be the whoever of wherever?” Timberlake looked into his glass of ginger ale for an answer, and then shook his head. “Wouldn’t you just rather be who you are than a version of somebody else? Wouldn’t you just rather be yourself?”

He was looking at me. Just when I thought that now might be the right time to say something—something man-to-man, something real, something that said let’s get the fuck out of here and go be monks, or at least take off and go drink in a place where we don’t feel like sellout bitches, where we can get away from The Twenty Thousand, from the blond actress, from the hordes of people like me—the blond stood up and walked three steps in his direction. She half-smiled in a way that not long ago I’d seen her do in a movie then whispered into his ear.

They left together. It was after 3 a.m. and Avery Street was finally dead enough for the most famous young man in the world to stand outside his hotel and smoke a cigarette with a less famous actress who bored him. From our table, I could see Timberlake through the window glass, bringing the cigarette to his lips and exhaling.

I bought a chicory coffee from a quiet woman in a banh mi shop, and drank it as I walked back through Chinatown to The Ritz, devising some way to cement our collaboration.

One idea: I’d heard him say the night before that he wanted to “work out” today. I could give him a boxing lesson and beat him down a bit, and he would understand that treatment as a testament of my integrity. Another idea: I could tear the covers off his bed, yell at the famous blond to get the hell out, and tell Timberlake it was time to get real, and stop fucking around.

Instead, I sat in the Ritz lobby, and wrote Melissa a groveling awkward letter explaining my enthusiasm to write about her cousin. Before sealing the letter, I tucked a $20 bill inside the envelope, to pay for my whiskey. I slid the letter under the door of room 1248.

Outside, I gave the valet my ticket—upon which was written the room number. The valet—a man two decades older than me with a Caribbean accent—studied my clothes, looked at me curiously then smiled. “Okay, man,” he said.

I asked him how much I owed him.

“No, no,” he said, waving his hand fearfully. “You don’t pay.”

I insisted. He refused. I insisted.

“One-hundred-twenty,” he said.

I gave the man $200—the amount, roughly, I’d made in two days of roofing—and told him to keep the change. When my truck emerged from the subterranean garage, I felt like myself again. I drove slowly north, one arm out the window. By afternoon, I was back at my mom’s house. My cousins from Thailand were visiting. My girlfriend came to meet them. She was still pissed. I told her what had happened, hoping it would justify my actions. It didn’t.

That fall, I was putting the finishing touches on my manuscript when I got a phone call from a number in New York City. I had moved into an apartment with my girlfriend, in downtown Portland. She was paying the rent because I had no money.

The call was from a literary agent. The caller, a young woman, said I was among a small list of writers who Timberlake had suggested he’d like to collaborate with on a potential book project. She wanted a writing sample. She wanted it today.

I looked down at my manuscript. “What about Monday?” I said.

“Today,” she said.

I sent what I had—a few articles I’d written on local bands in my hometown newspaper and a copy of my book manuscript.

A few days later, Antonio told me that Melissa had told him that Justin had told her that “I want to work with Coffin!” She also suggested that I be ready to tour in Asia, as the popularity of FutureSex/LoveSounds had found a new market overseas. I called my agent, who had suddenly started paying attention to me. “These things are usually up to the guy,” he said. “If he wants you, he’ll make it happen. It’s usually a 99/1 deal.” I asked him what that meant. “They get 99 percent of the money, you get 1.”

When my girlfriend got home from work, I explained the situation. All she said was: “You want to go back to Asia with him?”

I never heard from the literary agent. That winter, Antonio got released from his minor league team, broke up with Melissa, and I never saw her again. Justin Timberlake became more famous, and then more famous, until his long awaited next album earned him a performance at the White House. I, however, have remained pretty much the same: my girlfriend got pregnant, I became a father, we moved into an apartment in a somewhat dirty part of Portland. My book came out. It sold about 10,000 copies—not enough to make me famous. I sometimes wonder if Justin Timberlake ever read it.

Not long ago, I dug out the Air Force Ones that Melissa had given me. They were scuffed and dirty, and looked old. With little premeditation, I put them on a piece of newspaper in my driveway and spray painted them black. I wore them around like that for a week or so, even though the spray paint made them look like shit. A few days later, I put them on the curb next to a piece of paper upon which I’d written in capital letters: FREE.

Within an hour, they were gone.

Jaed Coffin is the author of A Chant to Soothe Wild Elephants, a memoir that chronicles his experience as a Buddhist monk in his mother’s native village in Thailand. He lives in Portland, ME.