Tales of monsters invading Japan are a longstanding tradition, usually involving menacing kaiju—literally “strange creatures”—rising from the sea to wreak havoc on a Japanese city. At this very moment, the country is engaged in just such a war, with an entire army of invasive creatures, but they’re both less fearsome and more adorable than Godzilla or Mothra. And they’re from North America, not the bottom of the ocean. They’re common raccoons, Procyon lotor. Sometimes real life is stranger than fiction.

Our story begins when a young Wisconsin boy named Sterling North adopts an orphaned baby raccoon and names him Rascal. The boy and the raccoon were inseparable as best friends, and for a year they did everything together. They fished the local streams and lakes, wandered the rural countryside together, and went for bike rides with Rascal riding in a basket attached to the handlebars. At the end of their year together, the young North began to realize that the raccoon was truly a wild animal, and not a pet. A critter that was once tame as a juvenile became more mischievous as he aged. The maturing male raccoon began to draw the attention of female raccoons and the aggression of other males. When North’s neighbors could no longer bear Rascal’s incursions into their fields and chicken coops, he knew that he would have to release his best friend. A life inside a cage—the only safe way to keep Rascal as a pet—was no life for a raccoon. North constructs a canoe and uses it to cross a nearby lake at the edge of a nicely wooded forest. There, he lets his best friend go, and returns home.

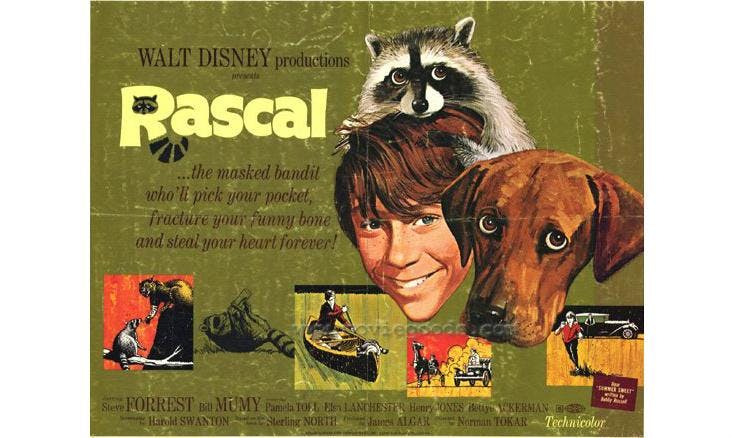

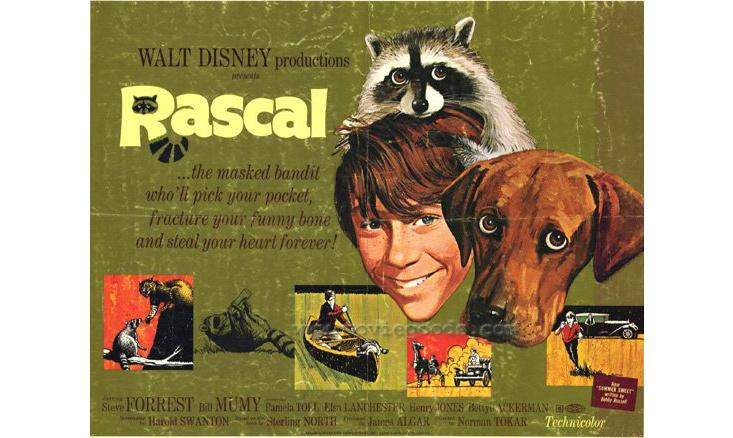

The true story of Sterling North and Rascal the raccoon formed the basis for North’s award-winning 1963 memoir, Rascal: A Memoir of a Better Era. In 1969, Disney would go on to create a feature film based on the book, predictably called Rascal, and a 52-episode anime series called Araiguma Rasukaru, based on the book, aired in Japan throughout 1977.

Once upon a time, raccoons were strangers to the island of Japan, save for the occasional critter kept in a zoo. That all changed when Araiguma Rasukaru aired and turned a nation onto raccoons’ inherent charm. “Its round, funny face with a bandit’s mask across the eyes and a striped bushy tail create a humorous impression,” writes Japanese researcher Tohru Ikeda of Hokkaido University, “and people find its habit of washing of food prior to eating curious.” Suddenly, every Japanese child wanted their own pet raccoon, like the boy hero of the cartoon. At the peak of their popularity, Japan imported more than 1,500 North American raccoons each year. The government eventually banned importing them or keeping them as pets, but it was too late.

Life imitated art when some of the Japanese children who had kept pet raccoons released their pets into the wilderness, like the boy in the cartoon and the real-life Sterling North before him. Other raccoons, being wild animals and not domesticates like dogs, cats, or horses, simply escaped. Still others were released out of frustration by their owners. Raccoons, like chimpanzees, are friendly when young, but as they age they become more aggressive, harder to control, and pose a potential threat to humans. Raccoons, like chimpanzees, are simply not suitable pets.

Suddenly, every Japanese child wanted their own pet raccoon, like the boy hero of the cartoon.

Raccoons have since proliferated in Japan, where they have no natural predators, and by 2004, they had spread at least 42 of 47 prefectures. . In some parts of the country, they invade cattle farms, where they feed on the same corn that gets fed to cows, and find safe spaces for reproduction in the tall grasses of grazing pastures. In other places, fish farms provide them with a veritable buffet. The animals damage crops across the food pyramid: corn, melons, strawberries, rice, soybeans, potatoes, oats, and more. In 2004 Ikeda and colleagues estimated that raccoons were responsible for more than thirty million yen (approximately US$ 300,000) worth of agricultural damage each year on the island of Hokkaido alone. Raccoons have also adapted to city life in the more urban parts of Japan, where they nest in air vents beneath floorboards, attic spaces of older wooden houses, Buddhist temples, and Shinto shrines. In cities, raccoons forage by going through human garbage, and hunt carp and goldfish that are kept in decorative ponds.

The masked invaders have also taken a toll on the ecology of Japan, preying on native mammals like the gray red-backed vole, along with snakes, frogs, dragonflies, damselflies, butterflies, bees, cicadas, and shrimp and other shellfish. They hunt the Japanese crayfish, a species classified as vulnerable by the Japanese Ministry of Environment, and the Tokyo salamander, which is threatened.

They compete both for food and for territory with the native raccoon dog (tanuki) and the red fox, and push native owls out of nesting spots in hollow trees. Ever since raccoons attacked a reproductive colony of grey herons in Nopporo Forest Park in 1997, the grand birds have not returned to their historic breeding grounds.

Raccoons are also important vectors for the spread of infection diseases. They’re known to carry rabies, and a 2011 report in the Journal of Parasitology even found evidence for the potentially dangerous and brain-altering parasite Toxoplasmosa gondii in raccoon droppings.

Following the passing of a law protecting native Japanese ecosystems in 2004, local governments began the culling of invasive raccoon populations. That year, Reiji Yoshida wrote in the Japan Times that Hokkaido would kill 2,000 raccoons each year. Predictably, there was public backlash to the harming of these cute, furry animals. “When the Kanagawa prefectural government announced the raccoon eradication plan in 2005, comments from the public revealed a wide range of opinions, including preference for control over eradication, negative response to lethal methods, skepticism of success, and opposition toward using great amounts of tax revenue for the plan,” said Harumi Akiba and colleagues in a 2012 paper in the journal Human Dimensions of Wildlife. Indeed, according to their survey of Kanagawa prefecture residents, only 31% of the population supported the complete eradication of invasive raccoons in Japan. Further, they discovered that Araiguma Rasukaru no longer held sway over the public perception of raccoons. More than half of the study participants had seen the series, but Akiba’s statistical models showed that it didn’t influence peoples’ support or rejection for raccoon culls. The anime series that had originally instigated the raccoon invasion itself has lost its control over public opinion.

This is one unfortunate consequence of fame. A species once beloved by a country’s children thanks to a popular cartoon, has in the space of just a few decades become a public nuisance, a source of significant agricultural economic losses, a possible vector for disease transmission, and a threat to other threatened and vulnerable species.

There is no good solution to the problem of invasive raccoons in Japan. Left uncontrolled, they will continue to cause problems. But the alternative—mass culls—doesn’t enjoy public support, and most research indicates that culls aren’t actually all that effective anyway. In the end, the best antidote against the anthropogenic origins of animal invasions is wildlife education. If more people understood that raccoons do not make good pets, no matter how adorable, Japan might not be in the unfortunate position in which they now find themselves, stuck between the rock of an invasive species, and the hard place of low public support for its eradication. Raccoons are best left in their natural North American habitats—and on TV.

Sterling North’s choice of name for his pet raccoon was perhaps prophetic, foreseeing the consequences of the mass adoption of an animal that was never meant to be a pet in the first place.

Jason G. Goldman received his Ph.D. in developmental psychology at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles and writes a blog called The Thoughtful Animal, hosted at Scientific American. His doctoral research focused on the evolution and architecture of the mind, and how different early experiences might affect innate knowledge systems.