Fame may be an unavoidable aspect of reality, an inherent part of the human condition, or just a quirk in the minds of some smart, social primates. In any case, it brings with it big problems. Here is the trouble with fame: It too often makes the recipient of it prone to hubris, and it even more often makes the rest of us blind to such hubris. Let me explain by way of an example. It’s all fine and dandy—if a bit unseemly—to spend time and emotional energy to follow the lives and personal exploits of famous people. I personally couldn’t care less about the “royal” baby of British fame, but I have been known to show some curiosity about the actors who have played Doctor Who, one of my favorite (British) television series. The problem is when we somehow forget that these are, well, actors (or singers, or whatever), and have therefore no expertise whatsoever outside of the type of endeavor for which they are famous (even discounting the absurd phenomenon of “celebrities” in the sense of people who are famous for being famous—a social tautology that says a lot about who we are).

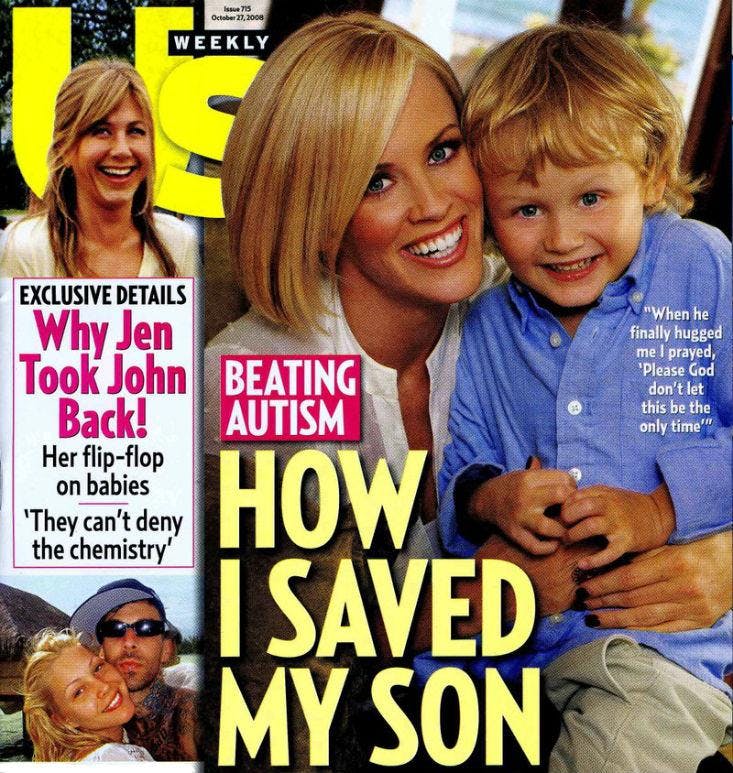

Take, for instance, the infamous Jenny McCarthy. She is a model (and later actress and “TV personality”), so her justified reason for being famous is that she is good looking. The problem is that McCarthy has also been pushing nonsense about vaccines somehow causing autism, a notion for which not only there isn’t a shred of scientific evidence, but against which militates a good number of peer-reviewed studies that have looked for it without finding it. Yet, despite her utter lack of scientific credentials, McCarthy has become an international icon in the “fight” against vaccination, a fight that is beginning to cause local outbreaks of childhood diseases that had not been a problem until recently (i.e., until the overwhelming majority of parents vaccinated their kids).

McCarthy has been known to respond to her critics that of course she understands science, because “Evan [her son] is my science,” as if the understandable grief of a mother confronting the onset of her child’s autism somehow were equivalent to controlled studies conducted by professionals on a large number of cases. When she is in a somewhat less positive mood McCarthy “refutes” scientific evidence by simply stating that it is “bullshit.”

What is astonishing in this tale of fame run amok is not that a mother with no scientific background convinces herself that vaccinating her child caused him to develop autism (thereby committing the well-known logical fallacy of post hoc ergo propter hoc), it is that so many people take her seriously on anything other than modeling (or acting, or “TV personality-ing”)—which, remember, is the reason she became famous to begin with. Why is this? I’m sure there is a number of concurring reasons, ranging from the dearth of scientific literacy and critical thinking in the population at large to the psychological propensity that some people have to be skeptical to the point of cynicism of whatever “establishment” (in this case, the scientific-medical one) is being attacked. But surely one of the reasons is fame itself: Too many of us, more unconsciously than not, simply draw from the fact that McCarthy appears on television and other media the conclusion that there must be something to what she is saying. Otherwise, surely, she wouldn’t be given so much attention? (You may notice yet another example of circularity in this type of reasoning…)

So here we have a case in which fame is troubling, not for the famous person (from what I hear, Ms. McCarthy is doing quite well in her life and career), but for society at large. Fame in these cases essentially short-circuits our critical faculties, leading us to accept propositions that would easily not pass muster if uttered by a non-famous person. Even more troubling, in this instance a large number of parents are actually acting on McCarthy’s suggestion, refusing to vaccinate their children, which in turn physically harms those very same children as well as the rest of society (because vaccines are effective at stamping out diseases only if almost everyone takes them, thereby precluding the disease agent from gaining access to additional biological hosts).

Of course, McCarthy’s is just one example among many, and unfortunately we can pretty much be guaranteed that hers won’t be the last one. Not until we learn to worship fame a lot less, and especially to make distinctions about the (usually very narrow) reasons one may be famous and the (potentially unlimited) areas where that famous person would serve us all so much better by just sparing us her unsubstantiated beliefs.

Massimo Pigliucci is professor of philosophy at the City University of New York. He is the co-editor (with Maarten Boudry) of Philosophy of Pseudoscience: Reconsidering the Demarcation Problem (University of Chicago Press). His philosophical musings can be found at www.rationallyspeaking.org.