A few weeks we asked you for your most unlikely stories—the kinds of things that make you scratch your head and think, “What are the chances?” Here’s one from one of Nautilus’ own editors.

Chanting can, apparently, be a pretty good marketing tool. It was chanting that turned me on to Reservoir Dogs, a cult movie by a then-little-known writer/director named Quentin Tarantino, in 1994. I was working as a junior counselor at an arts camp in Connecticut that summer. One day at lunch, two friends started chanting nonsense words, in unison and repeatedly, like some kind of tribal mantra. “Who-ka chocka, who-ka who-ka who-ka chocka, who-ka who-ka who-ka chocka,” they recited. Only after much prying on my part did they reveal that the chant came from a song (Hooked on a Feeling) that they’d heard in a movie (Reservoir Dogs). When asked what it was about, they obliged me, but sparingly and mysteriously, as if it were a secret club rather than any old flick. They described it as being so intense and raw that merely watching it—and if you’ve seen the movie, you must remember that scene—was basically a test of one’s manhood. Needless to say, I wanted to see it immediately.

While teenagers away at camp nowadays would probably have the thing downloaded in minutes, back in that bygone, pre-Web era, I had to wait several weeks until I was back home so I could head to the video store (yes, that was a thing) and rent the movie. After the first viewing, I was a fan (and had passed the manhood test). After the second and third viewings, which came hot on the heels of the first, I was ceaselessly repeating quotes from the movie—quotes in a language that was profane and macho yet also geeky. I was hooked. Soon I found out that I would have a chance to hear another story told in that language: Quentin Tarantino was soon to release another movie, and among fans of his, there was a lot of buzz about it. I made up my mind then that I would see it on opening night.

That night came just a few weeks later. Like nearly all movies, Pulp Fiction was to open on a Friday, the night of the Jewish sabbath. I was dead set on seeing the movie as early as possible, so I told my parents I wouldn’t be home for shabbat, knowing they would probably skip the usual reading of a Bible chapter that week with me gone. I headed off to a local theater with a group of friends and treated my ears to more of the strange, alluring language of Tarantino. (For the record, I was a little disappointed in Pulp Fiction upon first viewing. It had some painfully, masterfully tense scenes and some more of that great Tarantino language—Samuel L. Jackson’s brutally funny monologues stood out—but it seemed to me that much of it didn’t go anywhere. While Dogs was taut and compact, Pulp was at times meandering and indulgent. I liked it more in subsequent viewings, when I knew not to expect Reservoir Dogs II.)

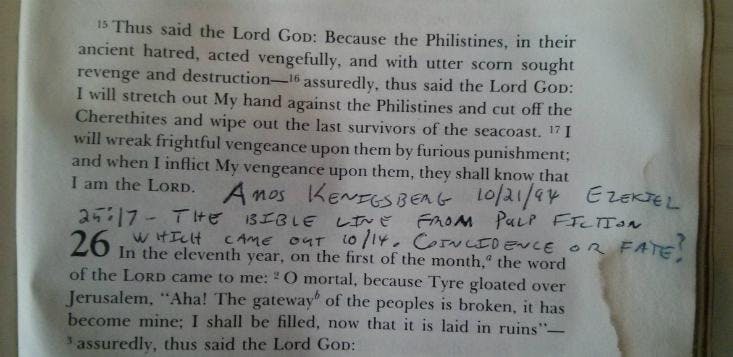

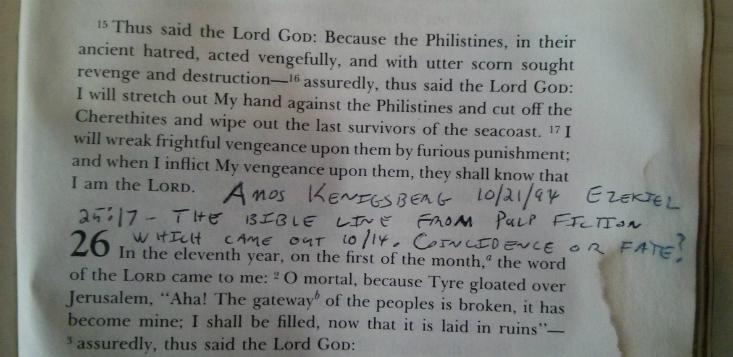

The next week, there was no big movie event for me, and I was back home for shabbat. My parents and I lit the candles, poured the wine, said the prayers. Each week we took turns reading, going through the Old Testament chapter by chapter, and that week’s chapter happened to be mine. As I finished reading it aloud, it seemed to sound familiar—like I had heard it before but couldn’t quite place it. I read it over again to myself and had a strange, funny thought, which I disregarded as being too improbable. I read it a few more times and couldn’t shake the notion. I eventually became convinced: The final verse of the chapter I was reading was the very same verse that Samuel L. Jackson’s character uses in Pulp Fiction as an ominous challenge right before he executes people: Ezekiel 25:17. Then, at the end of the movie, he undergoes a personal transformation and reinterprets the verse to have a very different meaning, completely changing his character and the climax of the movie. The verse was changed on its way to the screen, but it was still close enough to be recognizable.

This central quote from a film I had just seen, a movie I’d been waiting for with great anticipation, was indeed the ultimate verse from a Bible chapter that happened to be the very one that my family was up to the next week—a chapter I would have in fact read the week before, on the opening night of the movie, except for the fact that I had gone out to see that movie. As was our custom, I wrote my name and a short note at the end of the chapter, with what seems like notable understatement to my current self:

P.S.: That particular Bible book (called The Prophets, or Nevi’im in Hebrew) has a special meaning outside of the Pulp Fiction connection: It was inside my house when it was destroyed by fire in 1998. Damage from both smoke and water used to fight the fire is visible around the edges of the pages, and the cover was ruined, but the rest of the book survived.

P.P.S.: In case you’re wondering why my byline is different than the name on the Bible page, it’s because I changed my name when I got married.

Amos Zeeberg is Nautilus’ digital editor.