Earlier this month there was a rare announcement, promoted widely by the press: a new mammal species had been discovered, the first carnivorous mammal identified in the Americas for 35 years. But the olinguito, as the raccoon-like carnivore is now known, was not spotted for its surprising looks or remarkable behaviors that set it apart from other creatures. Rather, it was so similar in appearance to a related species, the olingo, that the National Zoo had an olinguito for years without knowing it. It was DNA testing that established that it is, in fact, genetically separate.

The oliquinto’s portrait is now all over the Internet. But it used to be that this type of news trickled into people’s consciousness, at least in Medieval Europe, with a distinctly different flavor, through illustrated bestiaries. In these books, animals were used to illustrate morals, in keeping with the contemporary idea that the natural world existed to educate humans about God’s will. Built from hearsay and modified as needed to tell the right fable, these beasts were not always intended to reflect physical reality.

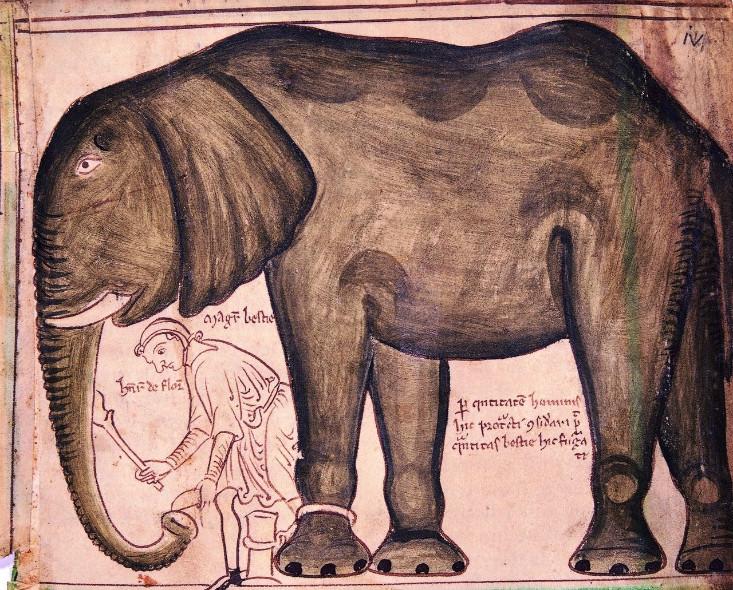

So when the news of unlikely new creatures—or, better yet, the creatures themselves—arrived in Florence or England or France, they may well have seemed to be dispatches from an allegory. Seeing a strange animal in the flesh, however, also sparked illustrators’ interest in depicting the real. When an elephant, given as a gift from the king of France to the king of England, arrived in London in 1255, historian and monk Matthew Paris created beautifully realistic drawings, evidently from his own observations. (For a great read about bestiaries and what they meant to people, check out this essay, “Medieval Bestiaries and the Birth of Zoology,” at The Antlion Pit. Also see Nautilus’ relevant story, “Monsters, Marvels, and the Birth of Science.”)

Eventually, realism began to outpace fantasy in depiction of new creatures. Marco Polo returned from his voyages to say that unicorns he had seen were not at all as advertised: “They are not of that description of animals which suffer themselves to be taken by maidens, as our people suppose, but are quite of a contrary nature.” He was referring to what we now call rhinos. And as the Renaissance began, the focus turned more towards what we would now call zoology, rather than theology-driven tales.

Today, when we hear of a new species, more often than not, as with the olinguito, it’s a matter of a DNA distinction, not a difference visible with one’s own eyes. It can make you feel a bit nostalgic for the days when a new creature might seem something of a monster, or a mythical beast.

Luckily, there are so many different species out there known only to specialists that a voyage of discovery is still possible. Do you know much about the goblin shark? Or the sea pig?

Do yourself a favor, if you’re ever feeling a bit burned out on new species that don’t seem much different from the old: Go to the local zoo. The marvels there are sometimes lost on children, who’ve seen images of these creatures since they were babies. But to an adult, endowed with an understanding of the aeons of life and death that went into making them as they are, a zoo’s denizens are pure magic. Just as people of earlier centuries might have marveled over God’s handiwork in the trunk of an elephant or the neck of a giraffe, we can gasp at what evolution has wrought.

Veronique Greenwood is a former staff writer at DISCOVER magazine. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Popular Science, and the sites of Time, The Atlantic, and The New Yorker. Follow her on Twitter here.