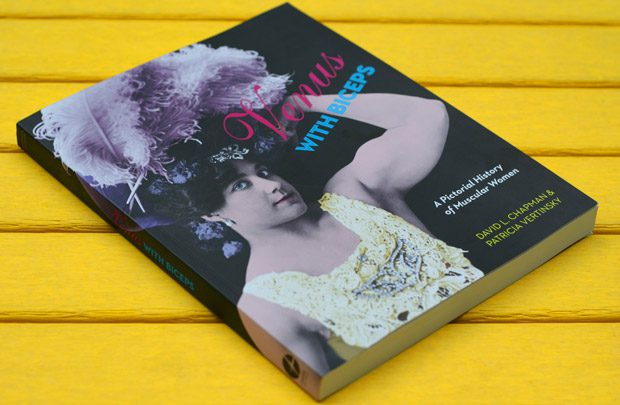

Having competed in amateur (a.k.a. drug-free) bodybuilding in my college years and to this day remaining the dedicated maintainer of a six-pack, I’m tremendously fascinated by the intersection of femininity and muscularity. So I was thrilled to come across Venus with Biceps: A Pictorial History of Muscular Women (public library) — a fascinating collection of rare archival images by David L. Chapman and Patricia Vertinsky 30 years in the making, chronicling nearly 200 years of sociocultural narrative on the strong female physique. These women expanded and redefined femininity itself, reining in a new era of relating to the will and the body, but their plight was and remains far from easy, carried out most prominently in the battlefield of popular imagery.

Having competed in amateur (a.k.a. drug-free) bodybuilding in my college years and to this day remaining the dedicated maintainer of a six-pack, I’m tremendously fascinated by the intersection of femininity and muscularity. So I was thrilled to come across Venus with Biceps: A Pictorial History of Muscular Women (public library) — a fascinating collection of rare archival images by David L. Chapman and Patricia Vertinsky 30 years in the making, chronicling nearly 200 years of sociocultural narrative on the strong female physique. These women expanded and redefined femininity itself, reining in a new era of relating to the will and the body, but their plight was and remains far from easy, carried out most prominently in the battlefield of popular imagery.

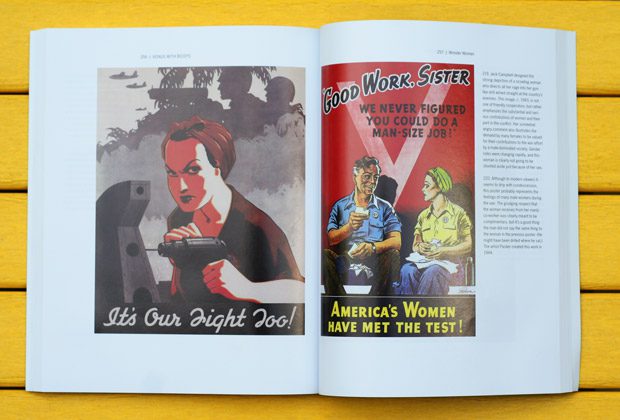

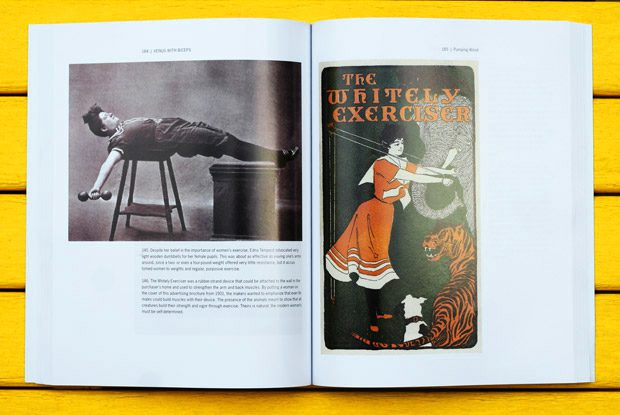

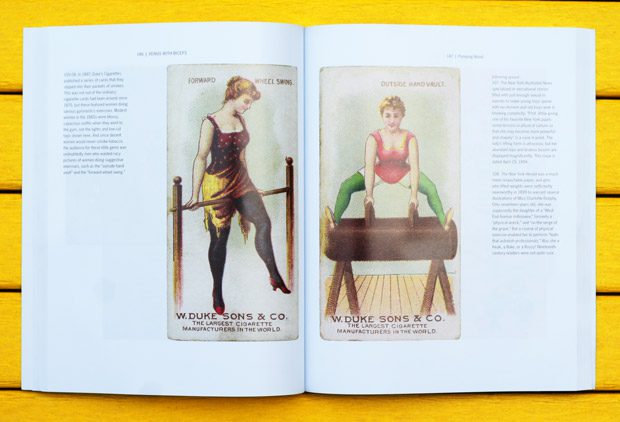

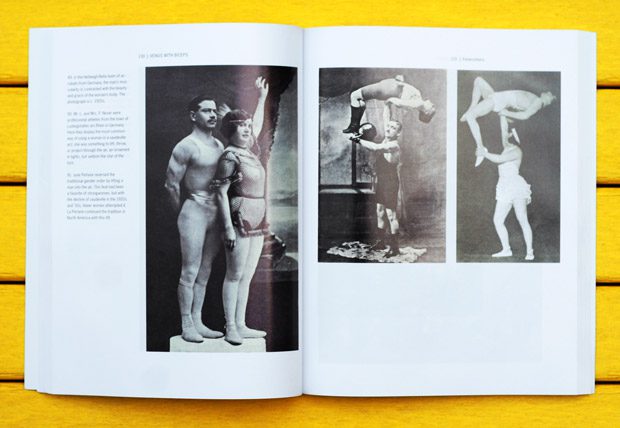

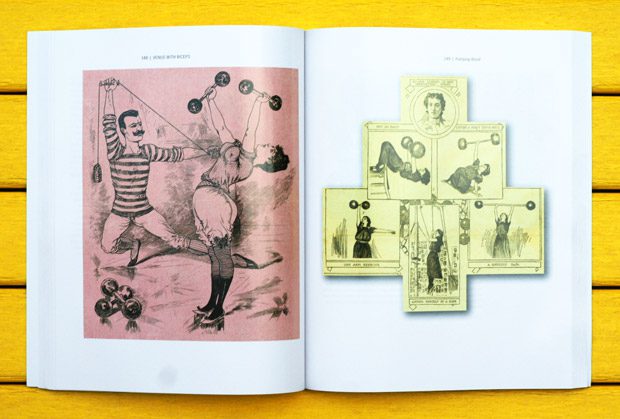

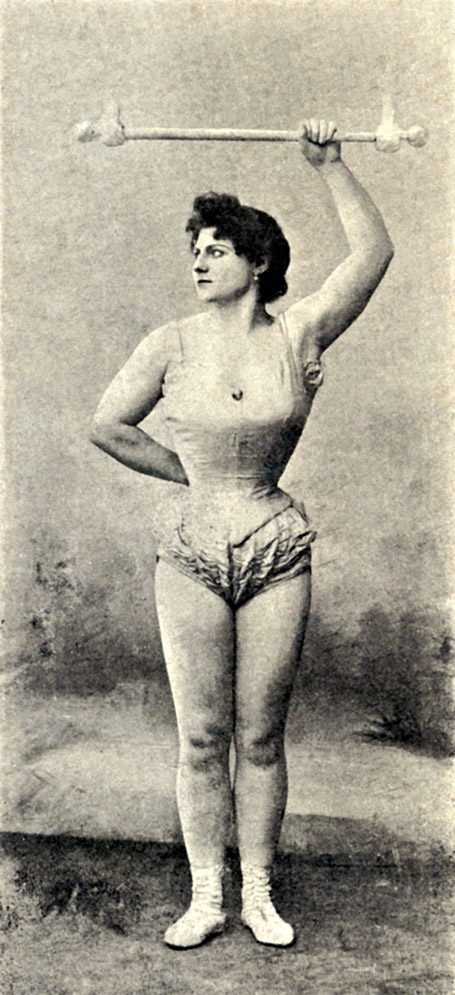

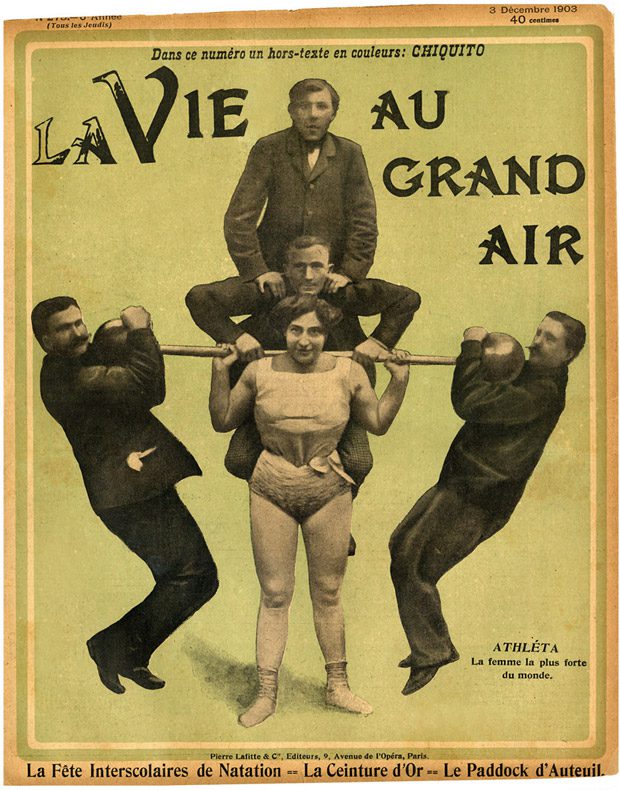

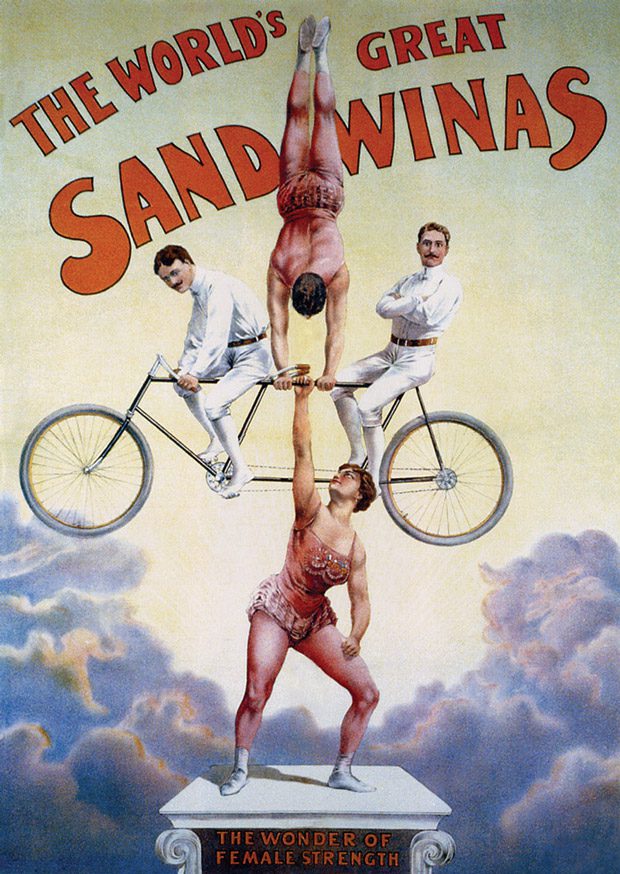

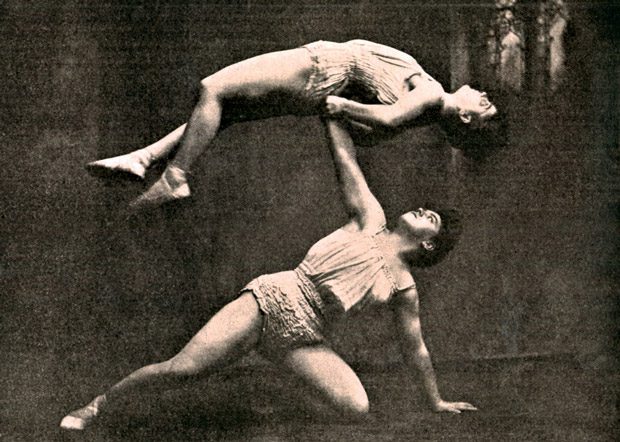

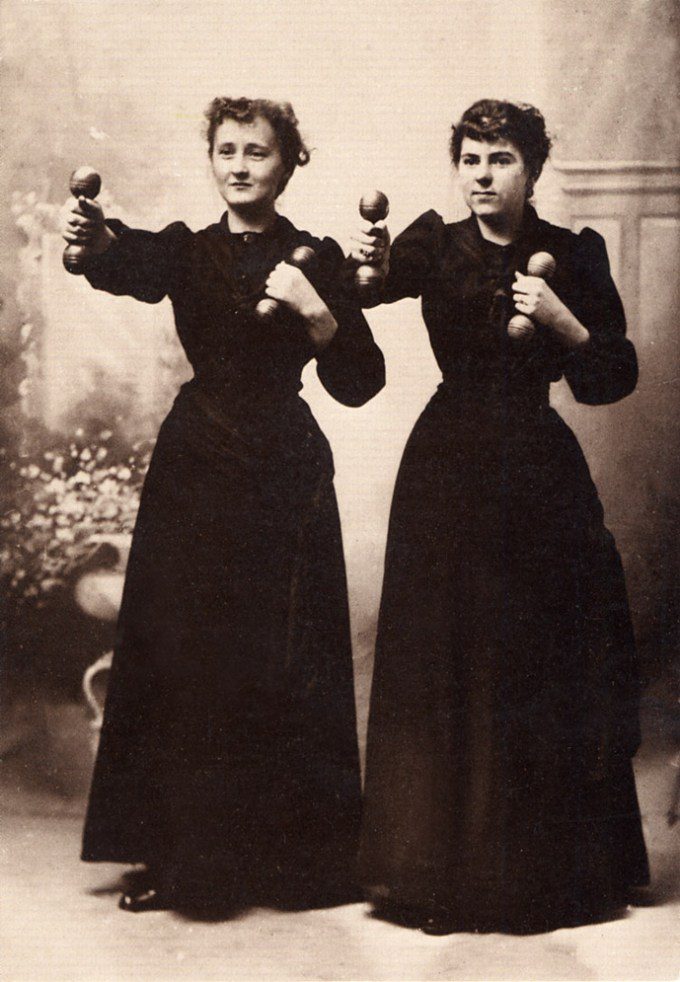

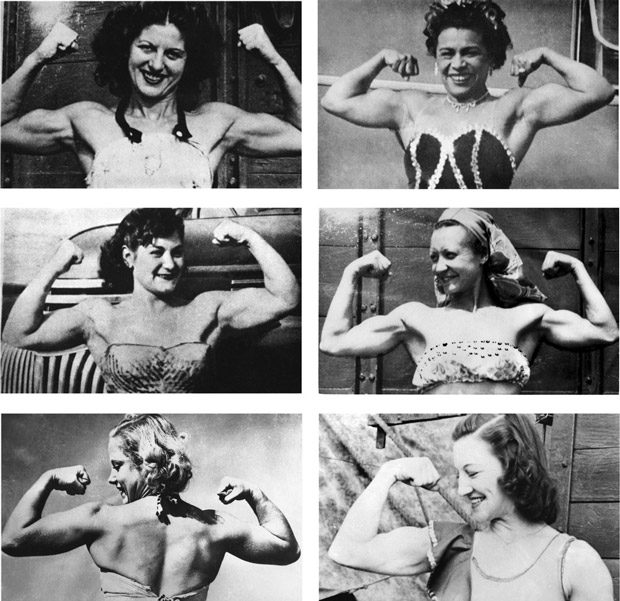

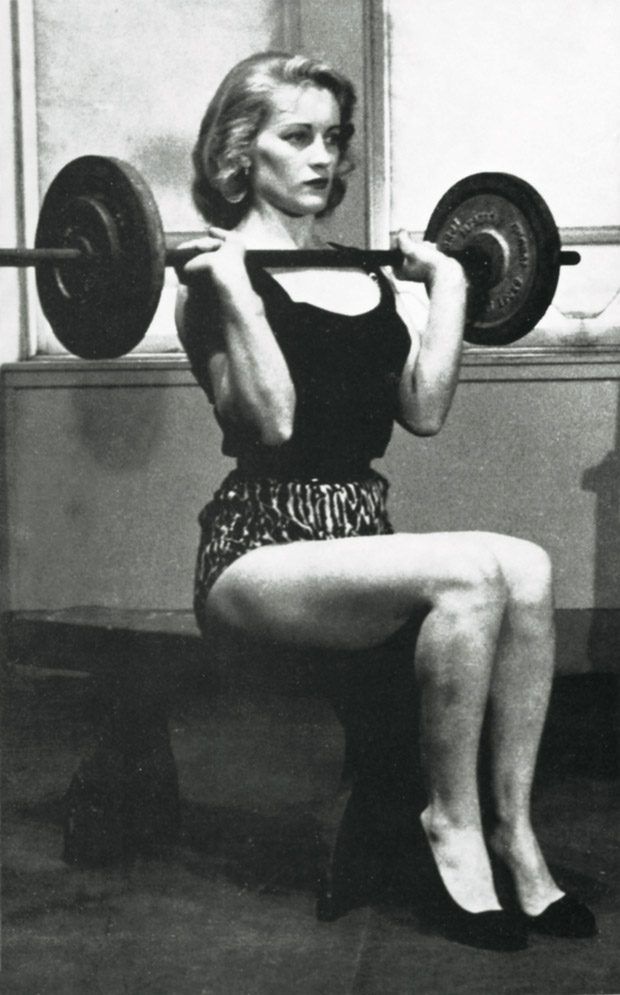

This treasure trove explores strongwomen’s legacy through rare posters, advertisements, comic books, flyers, and magazines, many never-before-published, for a total of two hundred fantastic full-color and black-and-white illustrations and photographs, framed in their intriguing and far from frictionless cultural context.

There is something profoundly upsetting about a proud, confident, unrepentantly muscular woman. She risks being seen by her viewers as dangerous, alluring, odd, beautiful or, at worst, a sort of raree show. She is, in fact, a smorgasbord of mixed messages. This inability to come to grips with a strong, heavily muscled woman accounts for much of the confusion and downright hostility that often greets her.” ~ David L. Chapman

The ambivalence about women and muscularity has a long history, as it pushes at the limits of gender identity. Images of muscular women are disconcerting, even threatening. They disrupt the equation of men with strength and women with weakness that underpins gender roles and power relations.” ~ Patricia Vertinsky

(On that note, see Wheels of Change: How Women Rode the Bicycle to Freedom (With a Few Flat Tires Along the Way).)

Created between 1800 and 1980, the images trace society’s conflicted relationship with muscular women, met with everything from fascination to erotic objectification to derision, and even moral admonition. (A 1878 article for The American Christian Review, for instance, outlined a nine-step path to sin and humiliation, down which women participating in sports were headed — a simple croquet game could lead to picnics, which led to dances, which led to absence from church, which engendered moral degeneration…poverty…disconnect…disgrace…and, finally, ruin.) Coupled with this is the permeating fear that a sculpted musculature would effectively “unsex a woman.”

Curiously, the period between 1900 and 1914 was a golden age for images of muscular women, but these images become mysteriously difficult to find in popular media, until about the 1970s. Chapman speculates the advent of cinema and other popular entertainment displaced fairs, circuses, and vaudevilles, a prime venue for strongwomen, causing these foremothers to gradually disappear.

Chapman’s inspiration for the book came from the confluence of two influences — his 1988 encounter with Muscle Beach icon Abbye “Pudgy” Stockton (1917-2006) and a 2000 New Museum exhibition titled Picturing The Modern Amazon. When Chapman was eventually invited to the museum to give a lecture on the iconography of strong women in historic images, he got a chance to meet some remarkable female athletes, which gave him new insight into these physique-builders’ psyches:

They aren’t building their bodies for us, anyway. The question is not whether they are sexually appealing for others but whether they excel at what they do for themselves. In the end, it is an issue of self-fulfillment. It was a simple explanation, but it made me wonder about the women who had tried to build their bodies in previous generations. Did they worry about gender-identity issues a hundred or more years ago?”

Ultimately, Chapman reminds us misconception, stereotype, and judgement of strongwomen are far from eradicated:

Many of the same battles that were being fought over a century ago are still being waged today… after all, labels are so much easier to deal with than realities.”

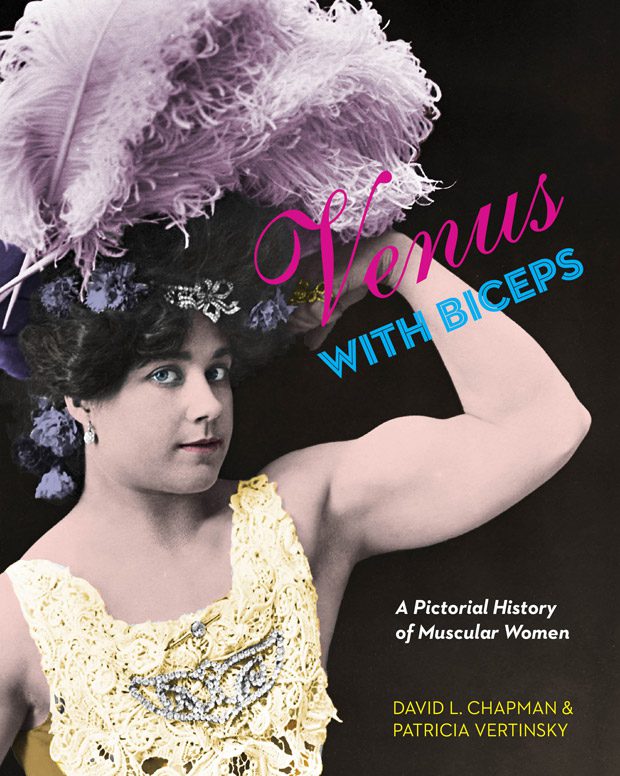

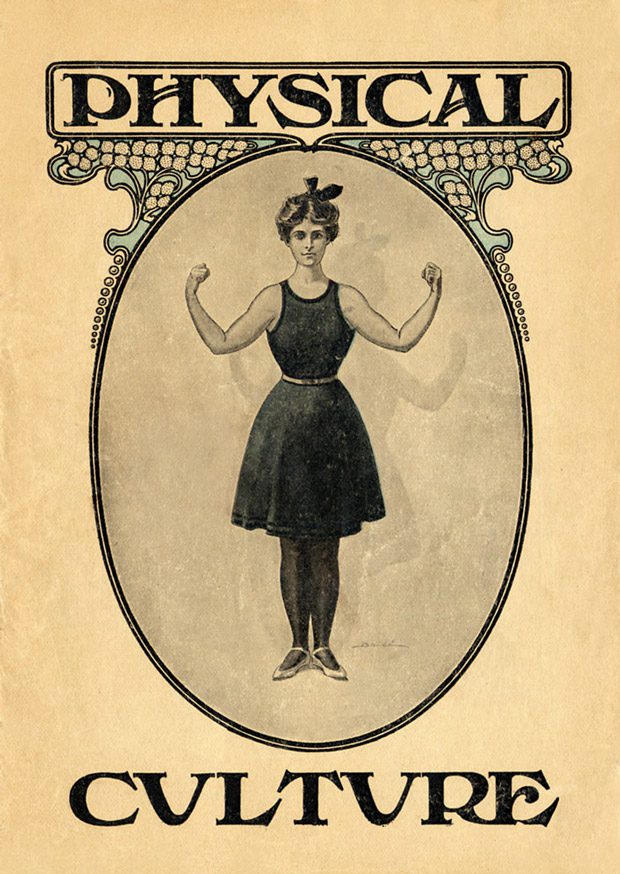

The woman on the cover, by the way, is the legendary aerialist Laverie Vallee, better-known by her stage name of Charmion. She is the subject of this rare Thomas Edison film from 1901, featuring her famous trapeze strip-tease:

Visually stunning, rigorously researched, and thoughtfully written, Venus with Biceps is as much a treasure chest of rare vintage ephemera as it is a fascinating and important meditation on a contentious facet of gender identity and cultural politics.

Images and caption text courtesy of Arsenal Pulp Press © 2011