I grew up in Bulgaria in the 1980s. Before the fall of the communist regime in 1989, scarcity underpinned the status quo — of commodities, of information, of opportunity. So limited were Western imports that once a year, around New Year’s, a handful of grocery stores would make available “exotic” produce like tropical fruit. The supply-demand ratio was so skewed that the store had to ration these exorbitantly priced annual luxuries — one banana and two oranges per person — and people would line up around the block to get them. (Meanwhile, the unworthy apple, Bulgaria’s most ample fruit crop, would sit neglected in the produce aisle at 50 stotinki a kilogram, roughly $0.15 per pound.) The most ambitious parents would camp out in front of the store overnight to make sure they got the bananas and oranges first thing in the morning as they went on sale.

I grew up in Bulgaria in the 1980s. Before the fall of the communist regime in 1989, scarcity underpinned the status quo — of commodities, of information, of opportunity. So limited were Western imports that once a year, around New Year’s, a handful of grocery stores would make available “exotic” produce like tropical fruit. The supply-demand ratio was so skewed that the store had to ration these exorbitantly priced annual luxuries — one banana and two oranges per person — and people would line up around the block to get them. (Meanwhile, the unworthy apple, Bulgaria’s most ample fruit crop, would sit neglected in the produce aisle at 50 stotinki a kilogram, roughly $0.15 per pound.) The most ambitious parents would camp out in front of the store overnight to make sure they got the bananas and oranges first thing in the morning as they went on sale.

In my lifetime, I’ve only seen such lines twice since — first in front of the Apple Store on June 29, 2007, when the iPhone was released, and then again in April of last year, when the iPad became semi-available. Under Steve Jobs, Apple became the bananas of the West.

In the 1990s, my mother joined Bulgarian Business Systems — Bulgaria’s first and, for over a decade, only official Apple dealer. I had grown up reading Jules Verne, so when we got our first Macintosh, I remember thinking that the man behind it — because, let’s face it, such was the cultural conditioning that I wouldn’t have expected a woman — must be some modern-day Jules Verne, having just handed me a portal for curiosity and exploration that helped me lean into knowledge in a way that has since become the fundamental driving force of my intellectual life.

That iconic 1984 Apple commercial, with its undertones of Big Brother rebellion and escapism, always had special resonance with me.

In the early 90s, about a year after I had started learning English, my mother reminds me of this jingle I wrote for a Macintosh Performa ad in one of the big newspapers:

An Apple a day keeps the doctor away

A Performa a day lets you thrive and play

(Oh come on, cut me some slack. I was nine.)

By the mid-90s, I was spending my school holidays folding Apple brochures and helping my mother set up the big annual Apple Expo, held every December at the Zemyata i Horata (‘Earth and People’) museum.

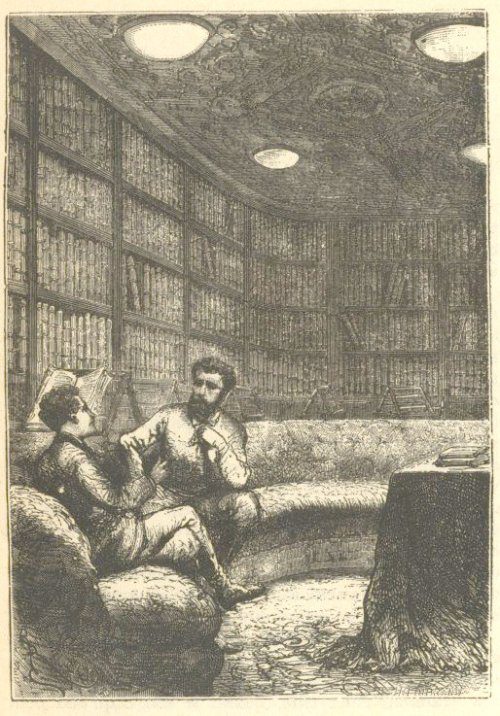

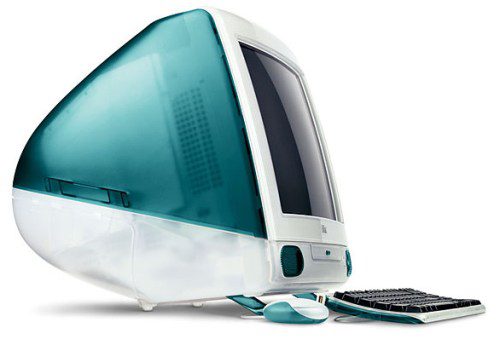

In 1998, my high school was the only school in the country to have Macs in its library. I vividly remember the day the first candy-colored iMac G3 arrived. It was the bondi blue flavor, the kind of translucent greenish-blue I’d always imagined as the backdrop to Captain Nemo’s world. When I was exploring the budding Internet on it, I felt like it had opened to me to the doors to the library on Nautilus.

When I came to the states for college, I went through a 13-month period I’ve since referred to as “the dark days” — being broke and beguiled by a sweet-talking UPenn senior, I bought his lightly used Dell laptop for the bargain price of $400, rationalizing it as a handy investment in class assignments. It was a foreign land to me, with its confusing navigation menus and counterintuitive interface. The blue screen became a frustrating frequent.

Finally, one fine day in 2004, I bit the bullet and walked into the campus bookstore, which had an official Apple section. I was working three jobs at the time, to pay my way through college, so I ended up eating canned tuna and store-brand oatmeal for a couple of months to offset the expense, but I did walk out with a brand new iBook G4. It was promptly named Francis by my friends, since I was going through my Frank Sinatra period and that’s all that streamed from my iTunes, the same iTunes through which I discovered Sinatra in the first place.

It was like I had undergone a personal Renaissance. I started taking Francis to all my classes and, often, classes I wasn’t actually enrolled in — curious lectures across various departments, from criminology to nutrition to design history, that I would drop in on. I never thought much of my secret hobby, until I heard Steve Jobs’s now-iconic 2005 Stanford graduation address. In it, he recounts the power of a serendipitous visit to a calligraphy class he wasn’t enrolled in, which went on to shape his landmark contributions to design and graphic interfaces:

If I had never dropped out, I would have never dropped in on this calligraphy class, and personal computers might not have the wonderful typography that they do. Of course it was impossible to connect the dots looking forward when I was in college. But it was very, very clear looking backwards ten years later. Again, you can’t connect the dots looking forward; you can only connect them looking backwards. So you have to trust that the dots will somehow connect in your future. You have to trust in something — your gut, destiny, life, karma, whatever. This approach has never let me down, and it has made all the difference in my life.” ~ Steve Jobs

Long before I was able to articulate it, he was a living testament to the power of networked knowledge and combinatorial creativity.

The semester I got Francis, I was one of three students to have a Mac in the large Annenberg Center lecture hall, where I had many of my classes. Over the next three years, I watched with wonder as the white lids proliferated, taking over the rows until, by my senior year, you could count on the fingers of one hand the students who hid in the back with their PCs. And it wasn’t because — or, okay, only because — to have a Mac was a status symbol of early hipsterdom. It was because it changed how we did everything, from taking class notes to designing presentations to listening to music. Most importantly, it changed our expectations about taking notes and designing presentations and listening to music.

This is the true legacy of Steve Jobs. He didn’t just transform technology, design, and entertainment — he transformed our expectations about technology, design, and entertainment. He not only made us eager to line up for the bananas of our time, but also made us willing to step into the Nautilus library of fascination and never want to leave.

Thank you, Steve, for shaping my childhood, my curiosity, and my creative and intellectual destiny. May you rest in peace 20,000 leagues under the sea.

* * *

Brilliant top image by Jonathan Mak