Nineteenth-century ideals of womanhood and beauty expressed as much about women as they did about the society in which they were germinated. At a time of radical sociocultural and economic shifts — rapid urbanization, new modes of transportation and communication, increasing mechanization of industry — the expectations for women’s role in society shifted as well, with an idealized version of what was known as “True Womanhood” underpinning pop culture representations of women in everything from newspaper advice columns to art.

Nineteenth-century ideals of womanhood and beauty expressed as much about women as they did about the society in which they were germinated. At a time of radical sociocultural and economic shifts — rapid urbanization, new modes of transportation and communication, increasing mechanization of industry — the expectations for women’s role in society shifted as well, with an idealized version of what was known as “True Womanhood” underpinning pop culture representations of women in everything from newspaper advice columns to art.

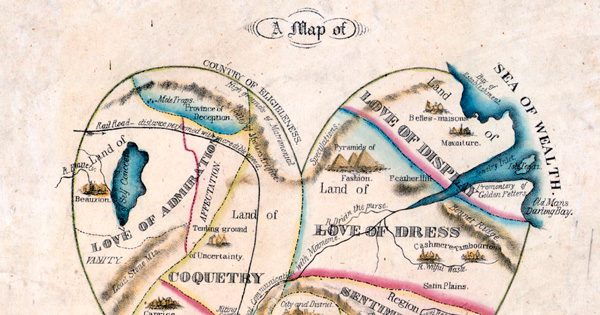

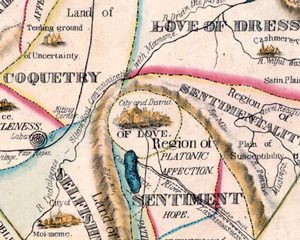

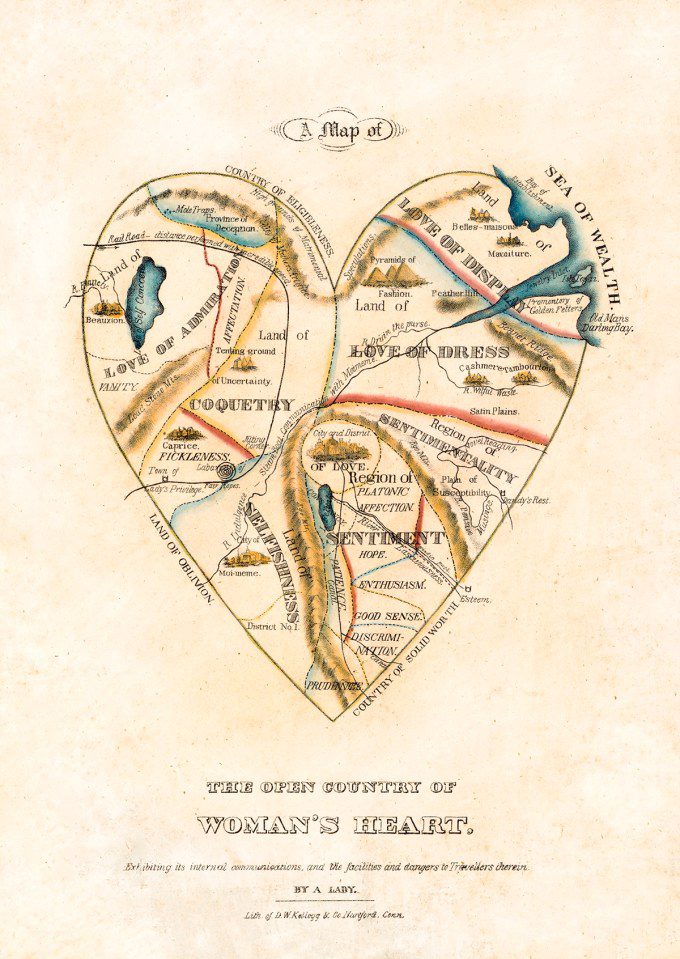

The work of an anonymous artist self-identified only as “a lady,” created sometime in the 1830s or 1840s in the long pictorial tradition of mapping the human condition and engraved by a Connecticut lithographer named D.W. Kellogg, The Open Country of a Woman’s Heart is subtitled “Exhibiting its internal communications, and the facilities and dangers to Travellers therein.” Though it mostly depicts Woman as a sentimental, selfish, and superficial being driven by vanity, it places Love at the center of her heart, with Good Sense, Patience, and Prudence at its tip — or bottom, depending on the interpretation.

For a fascinating look at the expectations of True Womanhood, marvel at Bernard O’Reilly’s 1883 classic The Mirror of True Womanhood: A Book of Instruction for Women in the World.