“Creativity is like chasing chickens,” Christoph Niemann once said. But sometimes it can feel like being chased by chickens — giant, angry, menacing chickens. Whether you’re a writer, designer, artist or maker of anything in any medium, you know the creative process can be plagued by fear, often so paralyzing it makes it hard to actually create. Today, we turn to insights on fear and creativity from five favorite books on the creative process and the artist’s way.

“Creativity is like chasing chickens,” Christoph Niemann once said. But sometimes it can feel like being chased by chickens — giant, angry, menacing chickens. Whether you’re a writer, designer, artist or maker of anything in any medium, you know the creative process can be plagued by fear, often so paralyzing it makes it hard to actually create. Today, we turn to insights on fear and creativity from five favorite books on the creative process and the artist’s way.

ART & FEAR

ART & FEAR

Despite our best-argued cases for incremental innovation and creativity via hard work, the myth of the genius and the muse perseveres in how we think about great artists. And yet most art, statistically speaking, is made by non-geniuses but people with passion and dedication who face daily challenges and doubts, both practical and psychological, in making their art. (And let’s pause here to observe that “art” can encompass an incredible range of creative output, from painting to music to literature and everything in between.) In Art & Fear: Observations On the Perils (and Rewards) of Artmaking, working artists David Bayles and Ted Orland explore not only how art gets made, but also how it doesn’t — what stands in the way of the creative process and how to overcome it. Fear, of course, is a cornerstone of those obstacles.

Despite our best-argued cases for incremental innovation and creativity via hard work, the myth of the genius and the muse perseveres in how we think about great artists. And yet most art, statistically speaking, is made by non-geniuses but people with passion and dedication who face daily challenges and doubts, both practical and psychological, in making their art. (And let’s pause here to observe that “art” can encompass an incredible range of creative output, from painting to music to literature and everything in between.) In Art & Fear: Observations On the Perils (and Rewards) of Artmaking, working artists David Bayles and Ted Orland explore not only how art gets made, but also how it doesn’t — what stands in the way of the creative process and how to overcome it. Fear, of course, is a cornerstone of those obstacles.

In the ideal — that is to say, real — artist, fears not only continue to exist, they exist side by side with the desires that complement them, perhaps drive them, certainly feed them. Naive passion, which promotes work done in ignorance of obstacles, becomes — with courage — informed passion, which promotes work done in full acceptance of those obstacles.

THE WAR OF ART

THE WAR OF ART

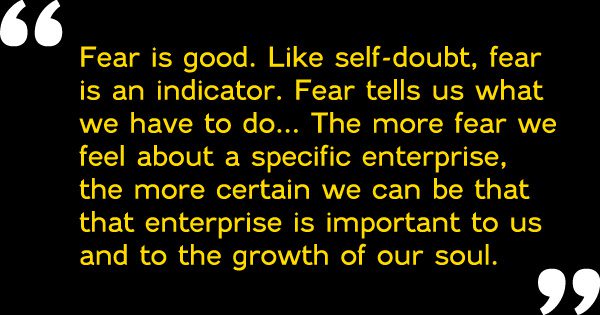

Steven Pressfield is a prolific champion of the creative process, with all its trials and tribulations. You might recall his most recent book, Do The Work, from our omnibus of five manifestos for life. But Pressfield is best-known for The War of Art: Break Through the Blocks and Win Your Inner Creative Battles, which tackles our greatest forms of resistance (“Resistance” with a capital R, that is) to the creative process head-on.

Steven Pressfield is a prolific champion of the creative process, with all its trials and tribulations. You might recall his most recent book, Do The Work, from our omnibus of five manifestos for life. But Pressfield is best-known for The War of Art: Break Through the Blocks and Win Your Inner Creative Battles, which tackles our greatest forms of resistance (“Resistance” with a capital R, that is) to the creative process head-on.

Are you paralyzed with fear? That’s a good sign. Fear is good. Like self-doubt, fear is an indicator. Fear tells us what we have to do. Remember our rule of thumb: The more scared we are of a work or calling, the more sure we can be that we have to do it.

Resistance is experienced as fear; the degree of fear equates the strength of Resistance. Therefore, the more fear we feel about a specific enterprise, the more certain we can be that that enterprise is important to us and to the growth of our soul.

THE CREATIVE HABIT

THE CREATIVE HABIT

There’s hardly a creative bibliophile who hasn’t read, or at least heard of, Twyla Tharp’s The Creative Habit: Learn It and Use It for Life. It frames creativity as the product of preparation, routine and persistent effort — which may at first seem counterintuitive in the context of the Eureka! myth and our notion of the genius suddenly struck by a brilliant idea, but Tharp demonstrates it’s the foundation of how cultural icons and everyday creators alike, from Beethoven to professional athletes to ordinary artists, hone their craft, cultivate their genius and overcome their fears.

There’s hardly a creative bibliophile who hasn’t read, or at least heard of, Twyla Tharp’s The Creative Habit: Learn It and Use It for Life. It frames creativity as the product of preparation, routine and persistent effort — which may at first seem counterintuitive in the context of the Eureka! myth and our notion of the genius suddenly struck by a brilliant idea, but Tharp demonstrates it’s the foundation of how cultural icons and everyday creators alike, from Beethoven to professional athletes to ordinary artists, hone their craft, cultivate their genius and overcome their fears.

There’s nothing wrong with fear; the only mistake is to let it stop you in your tracks.

Athletes know the power of triggering a ritual. A pro golfer may walk along the fairway chatting with his caddie, his playing partner, a friendly official or scorekeeper, but when he stands behind the ball and takes a deep breath, he has signaled to himself it’s time to concentrate. A basketball player comes to the free-throw line, touches his socks, his shorts, receives the ball, bounces it exactly three times, and then he is ready to rise and shoot, exactly as he’s done a hundred times a day in practice. By making the start of the sequence automatic, they replace doubt and fear with comfort and routine.

THE COURAGE TO CREATE

THE COURAGE TO CREATE

In 1975, six years after the great success of his wildly influential book Love & Will, existential psychologist Rollo May published The Courage to Create — an insightful and compelling case for art and creativity as the centripetal force, not a mere tangent, of human experience, and a foundation to science and logic. May draws on his extensive experience as a therapist to offer a blueprint for breaking out of our patterns of creative stagnation. Particularly interesting are his observations on fear, technology and irrationality, which might at first seem akin to the techno-paranoia propagated by Orson Welles and, more recently, Nicholas Carr, but are in fact considered counsel against our propensity for escapism, all the more relevant in the age of the digital convergence, nearly four decades after May’s insights.

In 1975, six years after the great success of his wildly influential book Love & Will, existential psychologist Rollo May published The Courage to Create — an insightful and compelling case for art and creativity as the centripetal force, not a mere tangent, of human experience, and a foundation to science and logic. May draws on his extensive experience as a therapist to offer a blueprint for breaking out of our patterns of creative stagnation. Particularly interesting are his observations on fear, technology and irrationality, which might at first seem akin to the techno-paranoia propagated by Orson Welles and, more recently, Nicholas Carr, but are in fact considered counsel against our propensity for escapism, all the more relevant in the age of the digital convergence, nearly four decades after May’s insights.

What people today do out of fear of irrational elements in themselves and in other people is to put tools and mechanisms between themselves and the unconscious world. This protects them from being grasped by the frightening and threatening aspects of irrational experience. I am saying nothing whatever, I am sure it will be understood, against technology or mechanics in themselves. What I am saying is that danger always exists that our technology will serve as a buffer between us and nature, a block between us and the deeper dimensions of our experience. Tools and techniques ought to be an extension of consciousness, but they can just as easily be a protection against consciousness. […] This means that technology can be clung to, believed in, and depended on far beyond its legitimate sphere, since it also serves as a defense against our fears of irrational phenomena. Thus the very success of technological creativity […] is a threat to its own existence.

TRUST THE PROCESS

TRUST THE PROCESS

More than 13 years later, Shaun McNiff’s Trust the Process: An Artist’s Guide to Letting Go remains a cocoon of creative reassurance that unpacks the artist’s process into small, simple, yet remarkably effective steps that together choreograph a productive and inspired sequence of creativity. Never preachy or patronizing, McNiff captures both the exhilaration and the terror of creating — and, more importantly, how the two complement one another, even in the face of fear.

More than 13 years later, Shaun McNiff’s Trust the Process: An Artist’s Guide to Letting Go remains a cocoon of creative reassurance that unpacks the artist’s process into small, simple, yet remarkably effective steps that together choreograph a productive and inspired sequence of creativity. Never preachy or patronizing, McNiff captures both the exhilaration and the terror of creating — and, more importantly, how the two complement one another, even in the face of fear.

The empty space is the great horror and stimulant of creation. But there is also something predictable in the way the fear and apathy encountered at the beginning are accountable for feelings of elation at the end. These intensities of the creative process can stimulate desires of consistency and control, but history affirms that few transformative experiences are generated by regularity.

When asked for advice on painting, Claude Monet told people not to fear mistakes. The discipline of art requires constant experimentation, wherein errors are harbingers of original ideas because they introduce new directions for expression. The mistake is outside the intended course of action, and it may present something that we never saw before, something unexpected and contradictory, something that may be put to use.