Forty years ago today, the Stanford Prison Experiment began — arguably history’s most notorious and controversial psychology experiment, which gleaned powerful and unsettling insights into human nature. Orchestrated by Stanford researcher Philip Zimbardo, the study randomly assigned 24 middle-class college-aged males, recruited via newspaper classifieds and pre-screened to have no mental health issues or criminal history, to the roles of prisoners and prison guards in a hyper-realistic simulated prison environment. Though the guards were instructed to under no circumstances harm the prisoners physically, they were encouraged to think of themselves as actual prison guards and instill in the inmates a sense of powerlessness, frustration and “arbitrariness,” to make them fully believe that their lives were controlled entirely by “the system” and that they had no freedom of action whatsoever.

Forty years ago today, the Stanford Prison Experiment began — arguably history’s most notorious and controversial psychology experiment, which gleaned powerful and unsettling insights into human nature. Orchestrated by Stanford researcher Philip Zimbardo, the study randomly assigned 24 middle-class college-aged males, recruited via newspaper classifieds and pre-screened to have no mental health issues or criminal history, to the roles of prisoners and prison guards in a hyper-realistic simulated prison environment. Though the guards were instructed to under no circumstances harm the prisoners physically, they were encouraged to think of themselves as actual prison guards and instill in the inmates a sense of powerlessness, frustration and “arbitrariness,” to make them fully believe that their lives were controlled entirely by “the system” and that they had no freedom of action whatsoever.

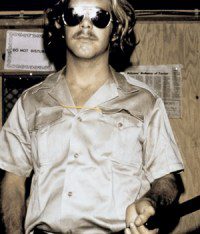

What followed was a devastating manifestation of the human capacity for cruelty and evil, so powerful and dehumanizing that the researchers had to end the two-week experiment after the sixth day. What’s most striking about the study is that all the participants were “normal” young men, yet they came to identify with their assigned roles so deeply that their behavior and entire personalities morphed to unrecognizable extremes, molded after the expectations of the respective role.

The study makes a very profound point about the power of situations — that situations affect us much more than we think, that human behavior is much more under the control of subtle situational forces, in some cases very trivial ones, like rules and roles and symbols and uniforms, and much less under the control of things like character and personality traits than we ordinarily think as determining behavior.” ~ Philip Zimbardo

Quiet Rage is a fascinating 1992 documentary about the SPE, written by Zimbardo himself and featuring archival footage of the actual experiment as well as interviews with the prisoners and guards conducted shortly after the study’s premature end. The 50-minute film is available online in its entirety — prepare to be hopelessly uncomfortable with both the experiment itself and the debriefing, which starts at around minute 32.

I really thought I was incapable of this kind of behavior, I was really dismayed that…I could act in a manner so absolutely unaccustomed to anything I would ever really dream of doing. And while I was doing it, I didn’t feel any regret, I didn’t feel any guilt. It was only afterwards, after I began to reflect on what I had done that this began to dawn on me and I realized that this was a part of me I hadn’t really noticed before.” ~ Mock Guard

I began to feel that I was losing my identity, that the person that I called Clay, the person who volunteered to go into this prison…was distant from me, was remote, until, finally, I wasn’t that. I was 416, I was really my number. And 416 was gonna have to decide what to do.” ~ Mock Prisoner

Though the experiment was essentially about how authority and power dynamics affect our capacity for evil, it’s also a powerful demonstration of a great many human psychological liabilities, from bystander effect as third-parties like parents, the priest, and even the researchers themselves accepted the prison as a prison rather than an experiment, failing to intervene and end suffering, to in-group-out-group bias as the inmates singled out the new replacement prisoner and began to treat him as a vilified “other,” to the painful cognitive dissonance of the guards, trying to later reconcile their atrocious actions during the experiment with beliefs they had about who they were as persons and as human beings.

It’s important not to think of this as prisoner and guard in real prison. The important issue is the metaphor ‘prisoner’ and ‘guard’ — what does it mean to be a prisoner, what does it mean to be a guard. And a guard is someone who limits the freedom of someone else, who uses the power in their role to control and dominate someone else, and that’s what the study is about.” ~ Philip Zimbardo

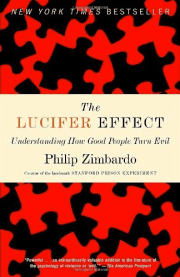

The study, as rattling and uncomfortable as it was, has connotations for everything from prison reform to conformity to self-improvement to violence, bullying and hate crime. For further insights from it, see Zimbardo’s excellent The Lucifer Effect: Understanding How Good People Turn Evil. Curiously, Zimbardo has since set out to explore the human condition from the opposite end of the good/evil spectrum, launching the Heroic Imagination Project — an effort to harness what psychology knows in advancing everyday heroism and the perpetration of good rather than evil.

The study, as rattling and uncomfortable as it was, has connotations for everything from prison reform to conformity to self-improvement to violence, bullying and hate crime. For further insights from it, see Zimbardo’s excellent The Lucifer Effect: Understanding How Good People Turn Evil. Curiously, Zimbardo has since set out to explore the human condition from the opposite end of the good/evil spectrum, launching the Heroic Imagination Project — an effort to harness what psychology knows in advancing everyday heroism and the perpetration of good rather than evil.

Another documentary about the SPE, The Evilness of Power, is available for free on The Internet Archive. Here’s a short excerpt, in which Zimbardo discusses the key takeaways from the study:

Above all, the SPE is a powerful case study in how easily we become identified with the roles and personas that have been assigned to us — by society, by our peers’ or parents’ or partners’ expectations, by our political leaders, and, perhaps most powerfully, by us ourselves. As soon as we begin to see ourselves as a “prisoner” or a “guard” (or a lawyer, or an alcoholic, or a victim, or a genius), we begin to act as one. Gandhi, it seems, had it right after all: